- Facebook96

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 96

I’m in Chicago for Poynter’s News Literacy Summit, entitled “Because News Matters.” Participants promote (to varying degrees) such outcomes as: following and understanding the news, taking informed action as citizens, understanding how the media work, critically interpreting news, understanding society and politics, valuing high-quality news, understanding media effects on individual behaviors and attitudes, being well informed about current events, civilly discussing controversial issues, valuing First Amendment freedoms, making news media, and making other forms of media.

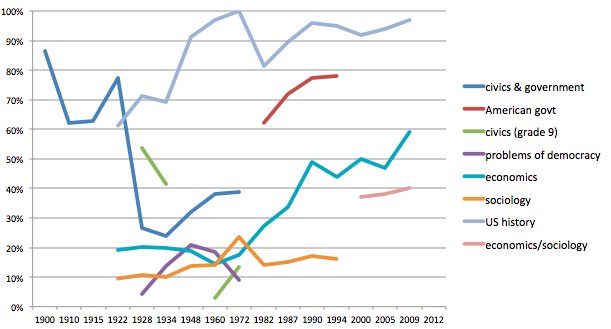

Each of these objectives has been pursued for a long time. John Dewey, for example, was a great proponent of news media literacy. To get a rough sense of what has been taught over time, consider this graph of the percentage of American students who’ve had various courses on their transcripts:

This is a complex picture, without simple trends. I would, however, emphasize a few observations:

1) A course that truly focused on using the news media was “problems of democracy,” which typically involved having to read the daily newspaper in order to prepare for pop quizzes on current events and classroom discussions. That course had its heyday in the 1940s and is now largely gone.

2) Courses that look like college-level social science are much more common today than they were in the past.

3) American Government is a hardy perennial course. But it has to cover a wide range of material, including the history and structure of the US government. Following current events is often an afterthought, not aligned with standardized tests.

Sources: Up to 1994, Richard G. Niemi and Julia Smith, “Enrollments in High School Government Classes: Are We Short-Changing Both Citizenship and Political Science Training?” PS: Political Science and Politics, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Jun., 2001), pp. 281-287. After that, the National High School Transcript Study; CIRCLE’s 2012 survey.