- Facebook339

- Twitter2

- Total 341

The Supreme Court of Spain has 79 judges. The Federal Constitutional Court of Germany has 16 members. The Constitutional Court of Italy has 15, but Italy is like many countries that also has a final appeals court for regular cases, and that tribunal is staffed by 350 judges.

I mention these examples in the context of arguments for “packing” our Supreme Court. Franklin Roosevelt’s effort to expand the court is usually presented as an example of executive overreach and a partisan ploy that backfired. But the problem with the current court is now critical.

Who would imagine that the following system could work? 1) One court has final jurisdiction over many fundamental issues that confront the society. 2) The public is divided over those issues. 3) There are two political parties, which hold incompatible views on those issues. 4) Justices appointed by each party regularly and predictably vote to decide cases in line with their respective party’s position. 5) Justices serve for life terms. 6) The president can nominate anyone he wants to be a justice. 7) A majority of the Senate must confirm. 8) The president and the Senate may be controlled by the same or by different parties.

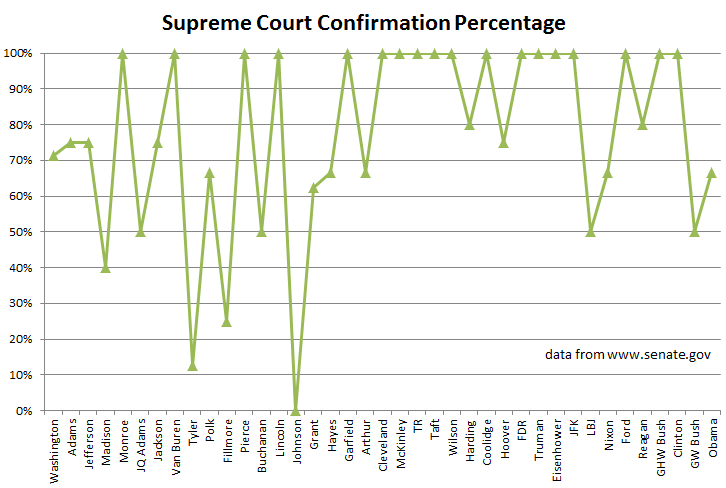

Once those eight conditions are in place, it’s more or less inevitable that presidents will be unable to replace Supreme Court vacancies unless their party controls the Senate, but when it does, they will be able to confirm virtually anyone they like to a life term. The defeats of Bork and Garland simply reflected opposition parties making rational decisions in the system they were given, and we should expect tit-for-tat from now on.

As I showed in a previous post, there have been periods when Supreme Court nominations have been uncontroversial. Those have been times of bipartisan elite consensus about constitutional questions. When that consensus has broken down, confirmations have been deeply contentious and the outcomes have been determined, to a large extent, by the luck of who controls which branch at which time.

If I could wave a magic wand, I would establish staggered terms for Supreme Court justices so that replacements become frequent. The stakes of each nomination would fall, and every president would be expected to have a strong but temporary impact on the court–as presidents influence the FCC. But this reform would require a constitutional amendment, since Article III, Sec. 1 decrees life terms.

An alternative is to change the number of justices. That is constitutional, since the number is set by a statute. But I’d change it a lot–to something like 25. Then turnover would be frequent, and the stakes of each appointment would be fairly low. I’d complement that change with a Senate rule that allows nominations to go through unless blocked by a super-majority.

In a large court, most cases are assigned to smaller panels–sometimes by lottery. There are reasonable processes for doing that. A larger court also has a much better chance of representing the diversity of the American people.

Letting the next president name 16 new justices seems a bit much (even if that president’s name turns out to be Joe), so I’d increase the size of the court by one seat every year for the next 16 years.

See also: reforms for a broken Supreme Court; is our constitutional order doomed?, are we seeing the fatal flaw of a presidential constitution?, two perspectives on our political paralysis, and the changing norms for Supreme Court nominations.