According to Freedom House, “Democracy faced its most serious crisis in decades in 2017 as its basic tenets—including guarantees of free and fair elections, the rights of minorities, freedom of the press, and the rule of law—came under attack around the world.”

This statement deserves unpacking if we want to understand in what ways democracy (or “freedom”) is declining worldwide. The statement combines several ideals that may not fit neatly together in practice. It’s not obvious why Freedom House mentions some rights instead of others. For example, if the key concept is “democracy,” we might look for equality of voice, power, and status. Finally, the statement never defines the alternative to democracy: what is gaining at the expense of the basket of values that Freedom House endorses.

I think what’s gaining is authoritarianism, meaning a system that relies on the arbitrary will of leaders. It is a government by rulers without (many) rules. An authoritarian leader can say “Do this” and can evade any explanation other than, “Because I said so.” Authoritarian leaders typically undermine precisely the values that Freedom House lists: fair elections, minority rights, a free press, and rule of law.

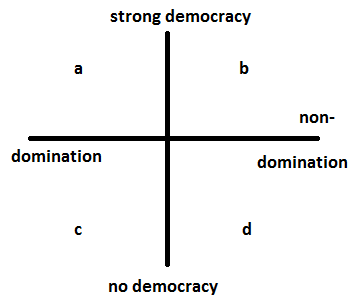

The opposite of authoritarianism is “non-domination,” in Philip Pettit’s influential sense. A system without domination is one in which, although citizens must follow rules and face restrictions, nobody can simply tell anyone else what to do. Pettit argues that non-domination was the core value in the long tradition of civic republicanism that began in antiquity and flourished in the Italian city states, the English Revolution, and the American founding. His framework suggests a spectrum that runs from an absence of domination (republicanism) to pervasive domination (authoritarianism).

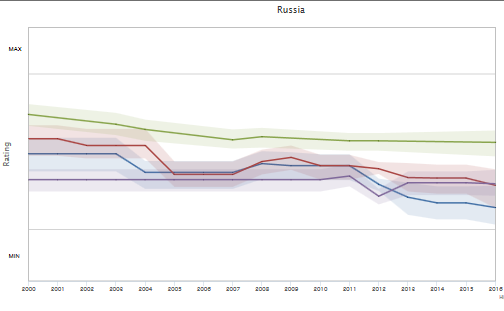

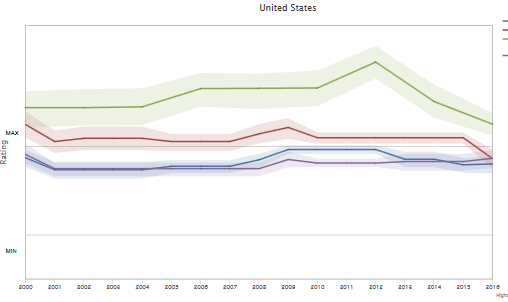

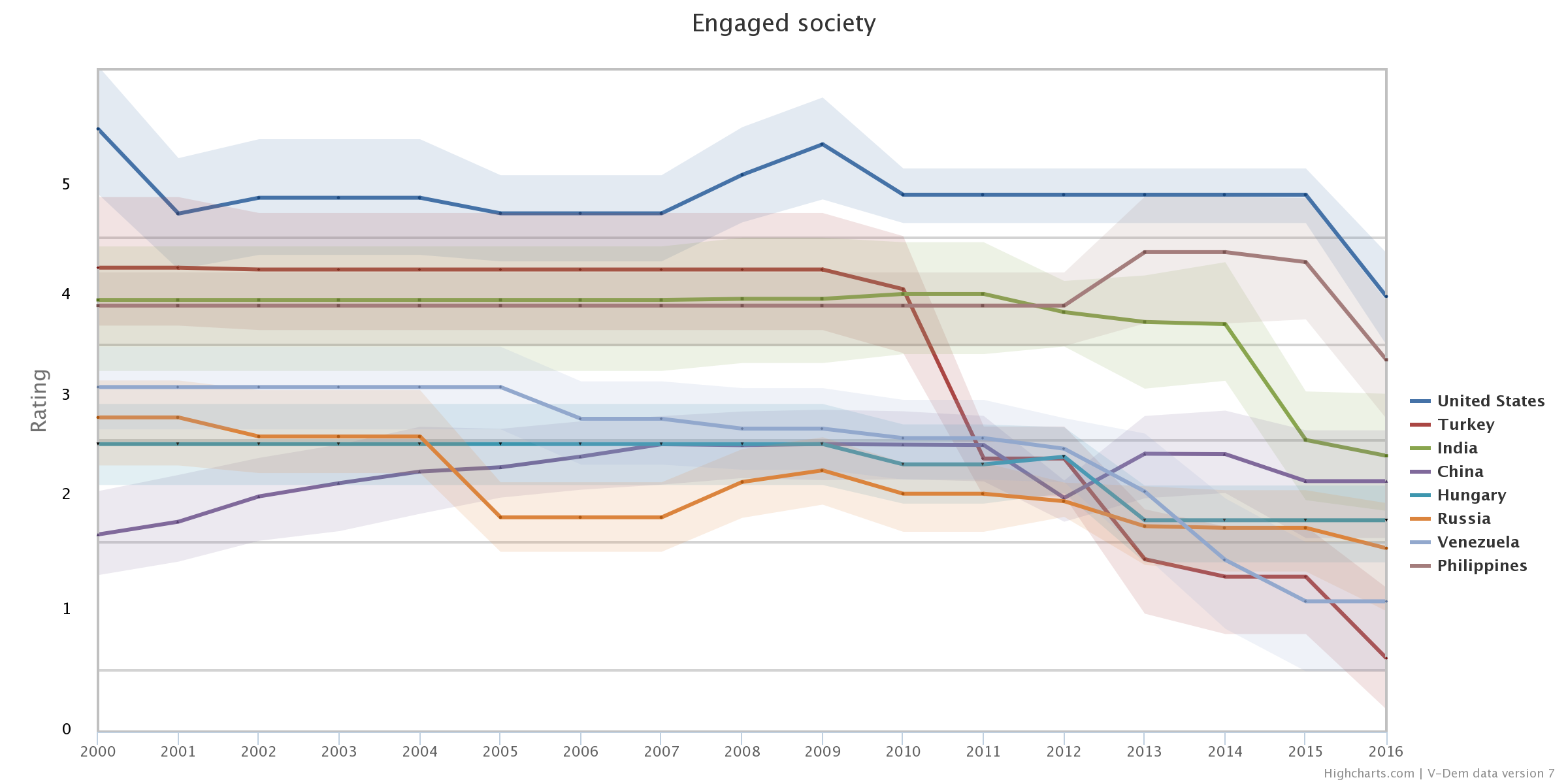

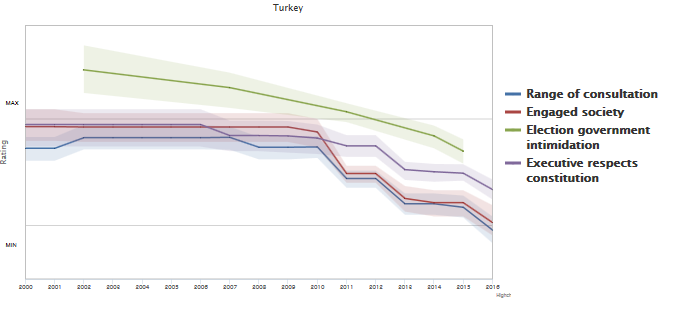

Evidence like the material I collected recently shows that republican institutions are in decline in many countries. Republicanism is in retreat.

Within the republican tradition, there is room for debate about democratic processes. Do democratic institutions (such as popular voting) prevent domination or create opportunities for majorities to dominate? There is also room for debate about liberal rights. For example, do property rights prevent or enable domination?

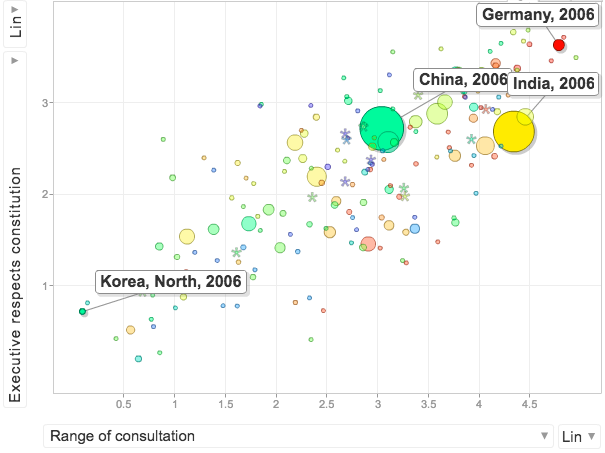

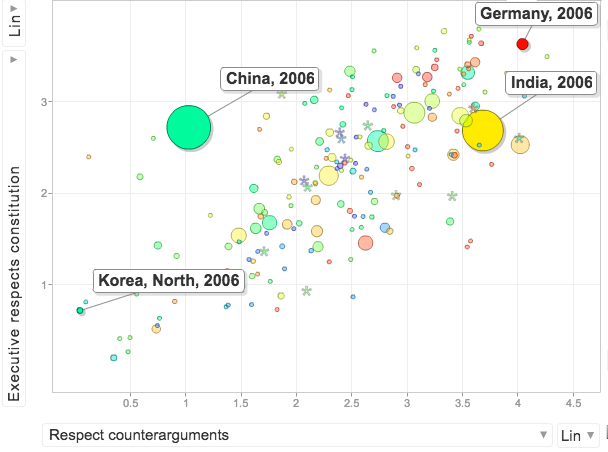

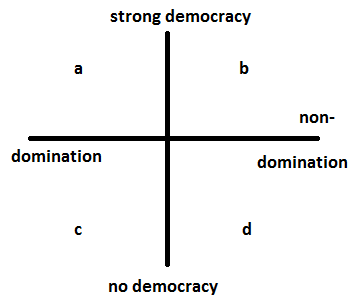

I’ll leave liberal rights aside for this post, although they are important. If we focus on democratic participation (lively debate, mobilized citizens, and a strong scope for elections), then we can view it as theoretically distinct from republicanism. Below, republicanism is on the horizontal axis; democracy on the vertical. Quadrant A stands for a system in which the people rule, yet majorities or popularly elected leaders dictate results without having to justify themselves. B is a society with equal voice and power, where everything is open to debate and no one can dominate anyone else. C is classic authoritarianism: no rules, no voice. And D is a system in which the government is limited and rule-guided and obligated to explain itself, but the people don’t have much of a voice. (Austria-Hungary in 1890?)

It is then an empirical question whether democratic processes tend to accompany republican safeguards. Is B common? Is it even possible?

In the V-Dem database, in 2016, for nations that held elections at all, there was a correlation of 0.4 between the degree to which the executive branch honors constitutional constraints and the degree to which free elections were held without intimidation.

There was a stronger correlation between respect for the constitution and robust public discussion (.53). (This means that that “large numbers of non-elite groups as well as ordinary people … discuss major policies among themselves, in the media, in associations or neighborhoods, or in the streets”).

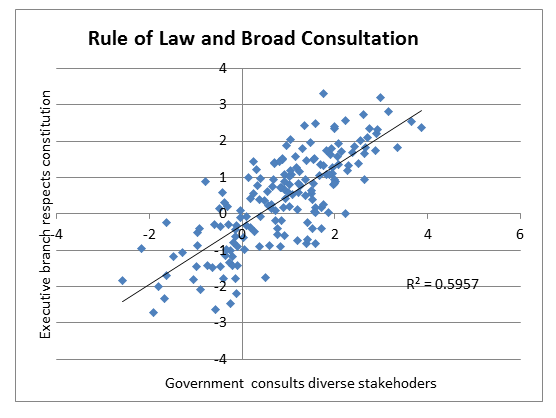

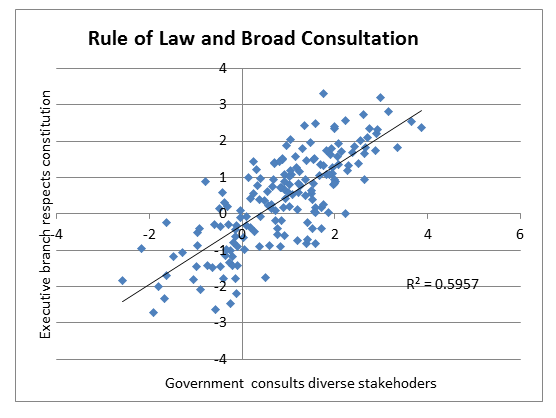

I show here the correlation between respect for the constitution and whether the government consults with a broad range of stakeholders before making decisions (0.6).

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that elections and a strong public sphere help to check arbitrary power. Perhaps limited governments are forced to permit elections, to consult with stakeholders, and to accept robust deliberation.

There are no examples in the world today of strongly rule-guided governments that don’t deliberate at all, nor are there any governments that consult and deliberate widely but pay no attention to constitutional safeguards.

However, the correlations are far from lockstep. Countries do fall in all of the four quadrants, albeit not deeply into A or D. If your values are strongly republican, democratic methods seem to be helpful–but they won’t get you all the way to non-domination. And if your values are strictly democratic, republicanism may get somewhat in your way.

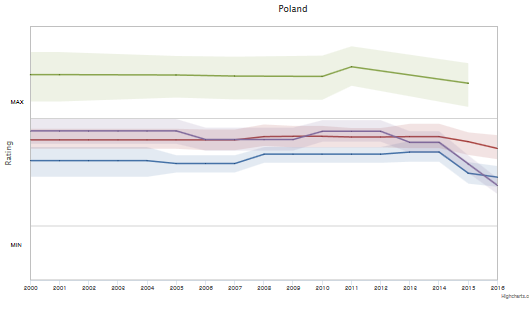

The pattern is less pronounced but similar in Poland since 2011.

The pattern is less pronounced but similar in Poland since 2011.