Tomorrow in DC, I’ll be on a panel with Sonal Shah from the White House Domestic Policy Council, Chris Gates from Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement, and Steve Gunderson, President and CEO of the Council on Foundations. The topic is “An Evolving Relationship: How Philanthropy and the Executive Branch Work Together to Promote Civic Engagement.” I’m supposed to address that topic for about 10 minutes. I haven’t decided what to say but I have a few notes.

In a fine paper on the this subject, Brad Rourke cites Michael Delli Carpini’s definition of civic engagement: “Individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern.” If that is civic engagement, how should the executive branch of the federal government and foundations promote it? I can think of several strategies:

1. They can fund opportunities for citizens to identify and address public concerns collaboratively. Professional public servants do that, and so do employees of many private companies, but somehow their roles aren’t addressed under the heading of “civic engagement.” Instead, foundations that support citizenship have often funded volunteering or non-career service jobs. Lately, the main source of financial support has shifted. Philanthropy has lost money in the stock market while the Corporation for National and Community Service–the federal program that funds volunteering opportunities–is on course to triple and has an annual budget approaching $1.5 billion.

In a way, the story is straightforward: foundations seeded various programs that are now growing because of federal dollars. But the Corporation is not allowed to spend any funds on electoral activities, even though political action meets the definition of “civic engagement.” (As does journalism and media-creation.) Instead, the Corporation has been charged with recruiting large numbers of volunteers to address several big, pre-defined social problems, such as the dropout crisis. That is a different way of thinking about “civic engagement” than we see when citizens define, discuss, and diagnose their own issues. So there is plenty of room for foundations to support participation that is more political or more deliberative, or both, than the Corporation does. Meanwhile, I would like to see the Corporation adopt civic learning objectives for all its participants.

2. They can draw national attention to issues of civic engagement. Citizenship is a contested topic: progressives, conservatives, and others have different opinions about it. But there is also some common ground, and I think our democracy would benefit from paying more attention to active citizenship–even if we continue to disagree about it.

The White House has tried to attract attention to civic engagement on several occasions. George H. W. Bush made it the theme of his inaugural address. President Clinton launched the New Citizenship Initiative in the White House Domestic Policy Council. President George W. Bush held a White House Forum on American History, Civics, and Service (which I attended and blogged about). Those are examples; more could be cited.

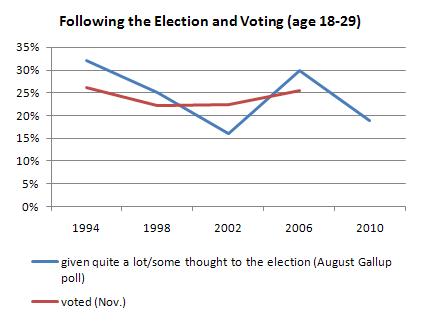

It’s my sense that today’s polarized political atmosphere would make presidential leadership on citizenship especially difficult. When people are willing to call AmeriCorps volunteers “Obama’s Brownshirts,” it’s difficult to have a reasonable discussion of civic engagement. And it’s a fact that two thirds of young American voters pulled the lever for Obama in 2008. That means that any concerted effort to get young people civically engaged will tend to draw the center-left, even if that’s not the intention.

The Clinton “New Citizenship” effort migrated to civil society when my then boss, Bill Galston, left the Domestic Policy Council and The Pew Charitable Trusts funded his National Commission on Civic Renewal. Although the issue of citizenship needs presidential leadership, it fits more comfortably in the nonprofit sector today and that creates an opening for foundations. The main recent example is the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of a Democracy, a bipartisan effort to address an important aspect of civic engagement.

3. They could reform government so that all Americans had better opportunities to influence and collaborate with public institutions. I think that is the most important goal, but it cuts against technocratic impulses on the left and anti-government assumptions on the right. Arnold Fege has shown that getting communities involved with schools was a major purpose of federal policy during the 1970s, but there is not much of a groundswell for that approach today. DC School Chancellor Michelle Rhee’s remark that “collaboration is overrated” is probably closer to the norm.

On his first day in office, President Obama signed an order on transparency, participation, and collaboration. He strongly endorsed the ideal of government collaborating with citizens. Since then, the transparency agenda–giving more people access to more public information–has made much more progress than participation or collaboration. Transparency is somewhat more clear cut than collaboration, and it has an active, organized coalition that is funded by foundations. Collaboration has no lobby, and philanthropy could help build one.

4. They could work to make sure that all young Americans are educated for active citizenship, a cause that will require research, policy reforms, funding, changes in teacher education, and partnerships with institutions other than schools. Civic education has been a low priority for the federal government and a major issue for only a few foundations. There is much more to be done.