I’ve been talking a lot lately with immigrants and practitioners who work with immigrants who are worried about obesity and are trying to develop programs that address the obesity epidemic. These conversations remind me that several years ago, I helped lead a group of high school kids–almost all new immigrants from Africa and Central America–in community research on that very issue. They made a short video that is quite engaging. Their website is down, but I found their product on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. You can click the little icon to make it play at full-screen size.

Monthly Archives: June 2010

’tis the season for board meetings

(Hartford, CT) I am here for a board meeting of the Paul J. Aicher Foundation, the fiscal agent of Everyday Democracy, which brought Study Circles to the US. On Thursday, I’ll be in DC for a board meeting of Street Law, Inc., which provides legal and democratic education to teenagers in the US and other countries. And then on Friday, I’ll stay in DC for the board meeting of the Charles F. Kettering Foundation, which studies deliberation and democracy in the US and abroad and originally launched National Issues Forums, among other experiments. It will be a week of listening, learning, and voting on budgets …

on multitasking and what’s really good in life

I am sympathetic to Kord Campbell, the addicted multitasker who is profiled in today’s long New York Times article entitled “Your Brain on Computers: Hooked on Gadgets, and Paying a Mental Price.” He and I are exactly the same age, we have similar family structures, and I, like Campbell, acknowledge an Internet addiction. A little dose of dopamine quite noticeably surges in my brain whenever I see a positive item of economic news, a favorable poll, or evidence that someone has read something of mine.

The research on multitasking predictably focuses on its consequences: What does the behavior cause? The scientific jury is out, but there are troubling suggestive findings regarding the impact on cognitive abilities and stress. This research is interesting but will never be adequate, because studying consequences begs the one really important question. So what if multitasking raises stress, and stress shortens life? So what if multitasking rewires the brain so that we can no longer concentrate on a novel or our kids’ homework? The primary question is: What should we do with our lives? If everything is just a means to something else, there is no basis to say that it matters how long we live or what we do with our time.

Obviously, I have no grounds to tell anyone else what is important in life. For myself, three ways of being loom large: Caring for other people and being cared for in return; becoming absorbed in another person’s world through fiction, film, or nonfiction prose; and immersing oneself in some creative activity. The last is what Mihály Csíkszentmihályi calls “flow,” and I like this operational definition: when you’re in “flow,” you are so absorbed you forget to eat lunch.

None of these ways of being is fully compatible with multitasking. You might be checking email 37 times/hour (the national average) in order to care for others, but that isn’t likely. Certainly, you are not immersed in another person’s world or in a creative activity.

I have no methodology for selecting the three most intrinsically valuable activities. I did not derive them from a deeper or broader principle, although that might be possible. They could easily be mere prejudices or subjective preferences on my part. Still, the fact that I cannot tell you what to admire and value does not mean that there is no right answer to that question. And even if we disagree about which ways of being are most intrinsically valuable, I think we can agree that checking your email 37 times an hour isn’t one of them.

(It disturbs me that I literally checked my email several times while I composed this blog post.)

the old order passes

- Facebook312

- Total 312

When Tocqueville visited America in the 1830s, civil society was predominantly composed of local, voluntary groups. They held regular face-to-face meetings. Their most important means for distributing information and opinions were newspapers (which were carried by the US Mail). Associations needed newspapers to communicate and they arose in response to the news. Thus, Tocqueville wrote, “There is a necessary connection between public associations and newspapers: newspapers make associations and associations make newspapers.”

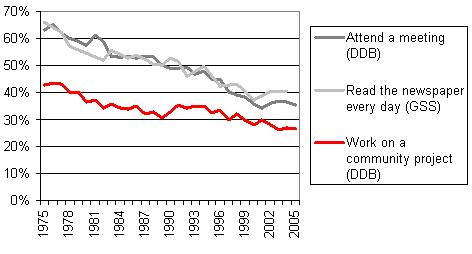

Tocqueville’s civic ecosystem evolved but remained fundamentally similar for more than a century. It is now in steep decline, as shown by these trends:

(GSS is General Social Survey. DDB is DDB Needham Life Style Survey. Analysis by the author.)

The correlation between the trends in newspaper readership and attendance at face-to-face meetings is especially striking. The reason to be concerned by this graph is a core commitment to public deliberation, which has traditionally occurred within associations, at meetings, informed by newspapers.

But we should not mourn the passing of 19th- and 20th-century associations and media. We should organize. We can rebuild the public sphere from new building blocks, as our predecessors have done several times in the American past. The new materials include digital technologies and networks, as well as new forms of face-to-face association.

AmericaSpeaks: Our Budget, Our Economy

My post for the day is over at usabudgetdiscussion.org, the blog for the National Town Meeting on Our Budget, Our Economy that AmericaSpeaks is organizing for June 26, 2010. This national deliberation will occur simultaneously in about 20 large venues “across the country, in many Community Conversations, and online.”

I conclude my post by saying, “I am confident [that citizens] will address this difficult, divisive, and complex topic just as they handle equally challenging questions at the local level–with maturity, civility, and collective wisdom. They will model a whole new form of politics that we desperately need.”