Numerous nonprofit groups are involved in mobilizing people to vote–usually focusing on poor, young, or minority Americans, who are least likely to participate. Other organizations fight legal barriers to voting. Often their objectives are progressive: they seek greater political equality so that policies will be more just. I certainly share these objectives, but I argue that we must look beyond voting and also consider how people directly address problems at the local level. Working on PTAs, tenants’ associations, and community development corporations; restoring ecosystems; organizing anti-crime patrols; and maintaining community websites are examples of fundamental democratic work.

1) We need such local, participatory efforts to address our deepest problems in areas like education, crime, the environment, and economic development. Large governmental institutions cannot solve these problems unless there is also strong local participation.

For instance, Harvard professor Robert Putnam finds that the level of adult participation in communities correlates powerfully with high school graduation rates, SAT scores, and other indicators of educational success at the state level. “States where citizens meet, join, vote, and trust in unusual measure boast consistently higher educational performance than states where citizens are less engaged with civic and community life.” Putnam finds that such engagement is “by far” a bigger correlate of educational outcomes than is spending on education, teachers’ salaries, class size, or demographics. (Robert D. Putnam, “Community-Based Social Capital and Educational Performance,” in Diane Ravitch and Joseph P. Viteritti, eds., Making Good Citizens: Education and Civil Society (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), pp. 69-72.)

2) There are big and widening gaps in local participation by social class. Therefore, anyone concerned about equity in our democracy must worry about participation in local community work, not just voting.

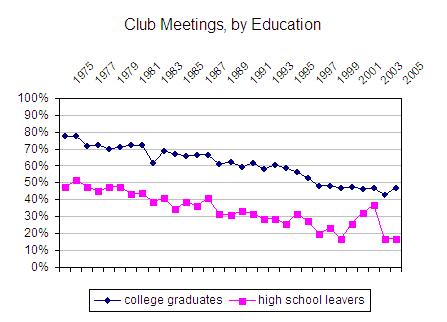

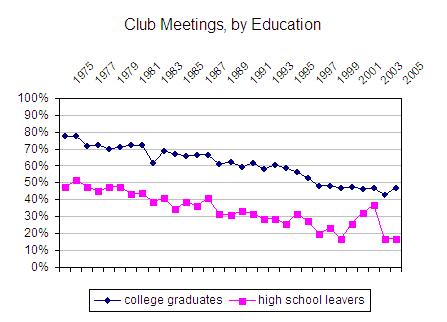

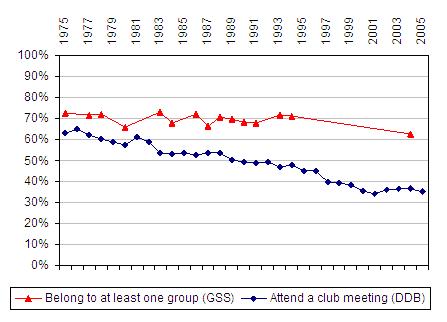

In the following graph, the dark blue line shows attendance at meetings for people with college degrees; the light blue line shows people without high school diplomas. The latter group is almost completely gone from civil society.

Put another way, half of the Americans who attend club meetings–and half of those who say they work on community projects–are college graduates today. Only 3 percent of these active citizens are high-school dropouts.

3) Voting isn’t attractive unless it emerges out of other forms of participation that give people information, confidence, motivation, and a feeling of connection to the community. People who vote are usually also members of groups and networks, community volunteers, and consumers of news media.

According to the 2000 National Election Study, there were strong positive correlations among reading the newspaper, volunteering, working on a community issue, contacting a public official; attending a community meeting; belonging to associations; and voting. To illustrate the relationships with an example: 42.4 percent of daily newspaper readers belonged to at least one association, compared to 19.4 percent of people who read no issues of a newspaper in a typical week.

4) Americans will not vote in favor of governmental programs, funded with their tax dollars, unless they believe that they can influence and collaborate with government institutions such as schools and the police. Therefore, progressives should be very eager to increase local participation.

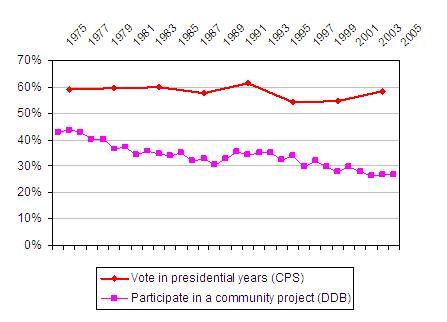

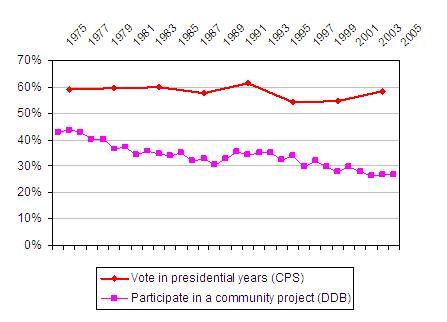

5) There has been no consistent decline in turnout since the early 1970s. (The voting rate is always too low, but it rises and falls depending on the issues of the day and the performance of major politicians.) However, there has been a consistent decline in local problem-solving and collaboration.

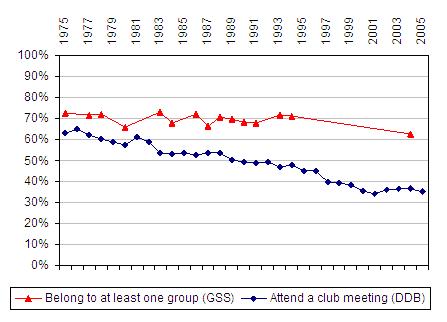

6) Probably one reason for the decline in face-to-face, public work at the local level is the change in the nature of our organizations. Theda Skocpol argues that non-participatory groups are replacing participatory ones. The graph below reinforces her finding. The red line shows that membership in groups is modestly down, but attending a meeting has declined much more substantially. In other words, people still join associations, but the groups they join don’t involve meetings. That means that people have less voice in civil society.

7) Despite the decline in the proportion of people involved in local problem-solving and hands-on work, this sector is very innovative and has great potential for growth. We see all kinds of successful projects, ranging from community blogs to the “21st Century Town Meetings” recently conducted in New Orleans; from youth advisory commissions to whole urban neighborhoods that have been rebuilt by church groups.

For examples and case studies, see Cynthia Gibson, Citizens at the Center (Case Foundation White Paper, Carmen Sirianni and Lewis Friedland, The Civic Renewal Movement: Community Building and Democracy in the U.S (Dayton: Kettering Foundation Press, 2005), Archon Fung and Erik Olin Wright, Deepening Democracy: Institutional Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance, and Community-Wealth.org.

If the premises presented above make sense, they imply that we need more collaboration among voting rights groups, groups that mobilize citizens to vote, and groups that promote civic innovation and collaboration at the local level. We should devote attention not only to inequalities and barriers in the formal political system, but also to other trends that may cut citizens out of public life. Two examples are the professionalization of advocacy and the excessive deference given to expertise in areas such as education, the environment, and economic development.

Finally, we need to consider policy reforms that take seriously the capacity of citizens to address problems. These reforms should go beyond thin conceptions of citizenship such as we see with the national service programs (Americorps and the like). Examples are here.