During a conversation with a friend on Wednesday, I realized why most contemporary literary criticism bothers me–from a moral perspective. (I use the word “moral” broadly, to mean any issue about how we should live or how our institutions should function.) Although there are some exceptions, whom I admire, most critics have moral agendas that they keep implicit.

Monthly Archives: June 2005

costs and benefits of voting

When you ask citizens why they didn’t vote, many say that the process was inconvenient and time-consuming. (See the table below, which uses 2002 Census survey data.) Their answers suggest that we could increase participation by making it easier to vote, e.g., by turning election day into a national holiday, by allowing early voting or voting-by-mail, or permitting citizens to vote online. But evidence from states that have adopted some of these reforms shows a modest impact. The Motor-Voter law, which was supposed to increase turnout by simplifying registration, did raise the registration rate but not actual turnout in elections.

I have come to think that answers to surveys like the following are misleading. After all, costs and benefits are two sides of the same coin. Someone who says that he lacked the time to vote is also saying that voting was not especially important to him. He actually had time; but other things seemed relatively more pressing. I think the turnout issue comes down to motivation. When issues seem important, when outcomes are uncertain, and when campaigns reach out to mobilize and inform voters, turnout goes up–as it did sharply in ’04.

| too busy, schedule conflicts | 27.1% |

| out of town, away from home | 10.4 |

| transportation problems | 1.7 |

| all time and convenience problems | 40.6 |

| not interested or felt vote would make no difference | 12.0 |

| did not like candidates or campaign issues | 7.3 |

| all dissatisfaction issues | 19.3 |

| illness or disability | 13.1 |

| bad weather | 0.7 |

| all special barriers | 13.8 |

| registration problems | 4.1 |

| forgot to vote | 5.7 |

| other reasons (not specified), don’t know, or refused | 16.5 |

the future of public broadcasting

I know quite a few people who work in and around public broadcasting; and over the years I have been involved in several behind-the-scenes projects with them. So my heart is with public radio and television. However, I wonder if there really is a future for federally-funded mass media. It seems to me that several major factors are working against it:

1. Liberals and conservatives both sincerely believe that the mainstream private media are strongly biased against them. This doesn’t mean that they are both right; but their feelings are genuine and deeply held. It’s difficult to influence Fox or CBS if you don’t like its prograns, but any organized group can apply political pressure to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Therefore, as long as liberals and conservatives feel victimized by most of the mass media, they will be sorely tempted to try to move CPB in a favorable direction. Trying to argue for “neutrality” or “balance” won’t protect public broadcasting, because there is no such thing as an ideologically neutral form of communication. Nor will it work to argue for “independence.” Some governing board must run CPB, and its members must somehow be chosen by politicians. Short of empanelling a jury of random citizens to manage public broadcasting, there is no such thing as “independence.”

2. Many Americans are moved by what I have called the “Jeffersonian principle.” Jefferson once wrote, “to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhors, is sinful and tyrannical.” It’s actually impossible to have a government without compelling people to fund the “propagation of opinions” that they dislike. For example, as long as we pay the salary of a president, he (or she) may say things we abhor. Nevertheless, Americans see a moral harm if they are forced to pay tax dollars for communications that they disagree with. It doesn’t matter how trivial the cost. Therefore, people will get much more angry about programming supported by CPB than anything on the commercial networks.

3. CPB has always had a top-down model: famous and distinguished people conduct a “peer review” processes to allocate funds. This is elitism, for better and for worse. It certainly doesn’t help to build a strong popular base.

4. A major rationale for public funding was the monopoly of the major networks ca. 1970. On its face, the media environment appears much more competitive and pluralistic today.

5. Much of the most creative “public media” doesn’t seem to need federal money or access to the broadcast spectrum. It consists of websites, low-power radio stations, blogs, podcasts, and other quasi-amateur work.

I’m torn between two strategic arguments. One says: All the grassroots, amateur media work is small potatoes. It’s destined for a niche market of hippies and hackers. We can work to grant low-power radio stations more rights and to relax certain intellectual-property laws to enhance the free sharing of information, but these reforms will have a marginal impact, at best. Ultimately, any great democracy must create an organized, mass public media space, of which the BBC is a classic example.

The other says: Congress will never appropriate substantial amounts of money for a broadcast system that’s of high quality and independent (whatever that would mean). Fortunately, many-to-many media like blogs can compete with mass commercial media, because the former are more creative and more fun. Thus the realistic strategy is not to worry about CPB but to put our energies into a media system that’s pluralistic, decentralized, and basically free of federal dollars.

the civic renewal movement (3)

In two recent posts, I began to describe the current movement for civic renewal. First, I listed some key elements of the movement; then I identified some common themes. In this last of the three posts, my topic is “the strength and growth of the movement.”

I am convinced that the civic renewal movement now forms a reasonably tight and robust network. My basis for that claim is the set of social ties that I observe as part of my official work, which involves numerous meetings and conferences in many parts of the United States (probably more than 75 per year). I am constantly struck by the appearance of the same people, or of people who know others in the broader network.

This is a mere impression. It could be tested with rigorous network analysis, which I believe would be quite useful. In brief, researchers would begin with several key organizations (such as the ones listed above) and ask decision-makers what other groups they collaborate with. Researchers would then move to those groups and ask, in turn, about their collaborations. Software can automatically generate network maps based on such data. I would hypothesize that a network map of civic renewal would show many links binding the whole field.

Lacking the resources actually to conduct such a study, I have used a very imperfect substitute. Instead of asking people to list their partners, I have examined electronic links among organizations? websites. Those links that are captured by the Google search engine can be depicted as a diagram. (Very regular readers may remember me doing something like this once before.) The image below shows major web links from three nodes–the National Allicance for Civic Education, the Deliberative Democracy Consortium, and the Pew Partnership for Civic Change–and from groups to which they link. I chose these three nodes as starting points because of my (highly subjective) sense that they represent important consolidations of practice since the 1990s. In particular, civic education and deliberation were fractious fields that began relatively late to form bridging networks?and then only as a result of rather careful and deliberate diplomacy.

Points on the graph represent organizational websites. Lines represent links among sites, as detected by an automated (and imperfect) Google search. I have written out the names of some of the points for illustrative purposes. The phrases in red are my generalizations about types of organization that cluster together.

Overall, the diagram shows a robust network: one can move by multiple paths from each sector of civic renewal to the others. I am certain that a more detailed process would reveal additional links. For example, I know that people in the civic technology sector (bottom left) work with people in service-learning (top left), even though the diagram shows no direct links.

It is important to note that the civic renewal movement may be robust and coherent, but it is insufficiently diverse. Most of the organizations listed above are predominantly, sometimes exclusively, white. Minorities are best represented in the work that involves community economic development; they are not well represented in civic education or in much of the deliberation field.

My second claim involves growth. I believe that the civic renewal movement is stronger, larger, and more influential than it was 10 or 20 years ago. This is a difficult claim to substantiate. When we work in social movements, we tend to make two historical assertions without hard evidence. To motivate ourselves and to win allies, we tend to assert that our problem is getting worse, and that a movement has recently formed to counteract it. Given the ?churning? that is endemic to American civil society, it is not obvious that the country?s civic condition really has declined or that a civic renewal movement has recently developed. Maybe every generation could make the same claims.

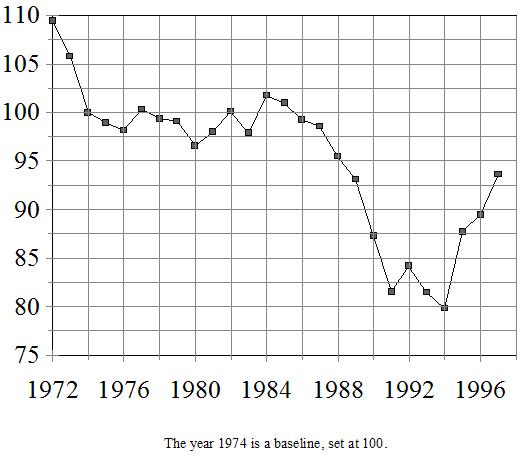

However, some aspects of civic life certainly have declined, and some new strategies and organizations certainly have formed to renew civil society. When the National Commission on Civic Renewal created an Index of National Civic Health (INCH) in 1999 (comprising 22 variables), we generated the trend line shown below.

I believe that the steep decline of INCH between 1984 and 1991?reflected in almost all of its 22 component variables?created genuine alarm and caused people to focus on civic renewal by the mid-1990s. For various reasons, including the work of these people, the situation had begun to improve by 2000. This is not to say that INCH includes all relevant variables or that there is consensus in favor of the proposition that ?civic health? had declined. But there was pretty widespread agreement, rooted in people?s daily experience, that we had a problem. (Unfortunately, I don?t have comparable data for after 2000, so I can?t continue the trend line after Sept. 11 and the first Bush Administration.)

If I were to tell story of the current civic renewal movement in America, it would incorporate the following developments and episodes:

the high school dropout problem

I’m at National Airport, on my way to Georgia to speak about the Civic Mission of Schools. I was just on Capitol Hill for an American Youth Policy Forum on high school dropouts. Paul E. Barton of the Educational Testing Service (ETS) gave a very useful presentation. Some highlights:

Growing numbers of 16-year-olds are taking the GED instead of finishing high school. It’s unclear why: they may be “pushed out” (encouraged to leave school so that they won’t count in dropout statistics or cause disciplinary problems), or they may be “drawn out” by the prospect of a high-school equivalency degree without all those boring and demeaning courses and dangerous school hallways. Obviously, it would be best to make high schools more rewarding for more kids. However, I wonder whether it would help to create a tougher, more highly valued exam as alternative to the GED; this could truly substitute for a high school diploma. Then kids who were ready for work or college at 16 or 17 could finish early and have decent prospects.