I spent today listening to kids–16 boisterous, funny adolescents from the nearby high school. We had recruited them to talk about their experiences as immigrants (or migrants), and how their eating habits had changed as they had moved to Maryland from West Africa, Central America, the West Indies, the Philippines, or Washington, DC. We taped the whole day so that a smaller group of volunteer students will be able to shape the best parts into an audio documentary on immigration and food. This is the latest stage of our National Geographic project on nutrition.

The parts of the discussion that will find their way into the documentary will be about recipes, memories of meals, shopping and cooking, and health concerns. For today’s blog, I’d like to report on a different topic, a digression. Most of the immigrant kids agreed with one who said: “Living in St. Lucia, I thought [the US] was the great land of opportunity. I never thought it was heaven, like some people do; but if you work hard, you can achieve anything.” (This is a close paraphrase, not a precise quote). When an adult asked if the kids thought that poverty came from laziness, they resisted that thesis, but they kept coming back to it. “If you really want to get something, you can do it. There was a homeless person who went to Harvard.” They acknowledged that there were insurmountable barriers to economic success back in their home countries–for example, the tuition required to attend elementary school. But in the US, success “depends on a person’s drive.”

The same theme of self-reliance and personal responsibility returned when they discussed fast food. “It’s your responsibility what you eat. After all that healthy food back home, you see a big hunk of meat [at McDonalds], you know it’s gotta be bad for you.” One young woman said that advertising could influence people to eat fast food. “Yeah, but that’s your fault cause you can’t control yourself.”

A student from Cote D’Ivoire said that back home, people viewed African Americans as lazy, and white Americans as “slave-drivers.” She said, “I don’t think America is that great of a place, but I do think freedom of speech and freedom of religion–a lot of places don’t have that.”

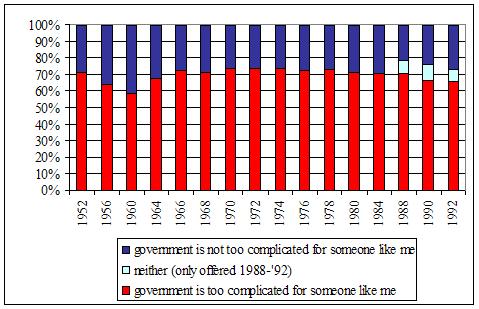

I think there must be something to this theory. Between 1952 and 1992, the National Election Study (NES) asked people whether they agreed with the following statement: “Sometimes politics and government seem so complicated that a person like me can’t really understand what’s going on.” Generally, people have found politics too complicated–or at least, have doubted their own capacity to understand it. However, the results do not show a lot of decline in Americans’ sense that politics is too complicated for them. The trend is pretty flat. Unfortunately, the question was dropped in 1996, and it changed a bit in 1988, when people were offered the option of refusing both choices (“too complicated” and “not too complicated”). If we assume that the people who chose “neither” would otherwise have said “too complicated,” then there was an erosion of confidence after 1984. But that’s a big assumption.

I think there must be something to this theory. Between 1952 and 1992, the National Election Study (NES) asked people whether they agreed with the following statement: “Sometimes politics and government seem so complicated that a person like me can’t really understand what’s going on.” Generally, people have found politics too complicated–or at least, have doubted their own capacity to understand it. However, the results do not show a lot of decline in Americans’ sense that politics is too complicated for them. The trend is pretty flat. Unfortunately, the question was dropped in 1996, and it changed a bit in 1988, when people were offered the option of refusing both choices (“too complicated” and “not too complicated”). If we assume that the people who chose “neither” would otherwise have said “too complicated,” then there was an erosion of confidence after 1984. But that’s a big assumption.