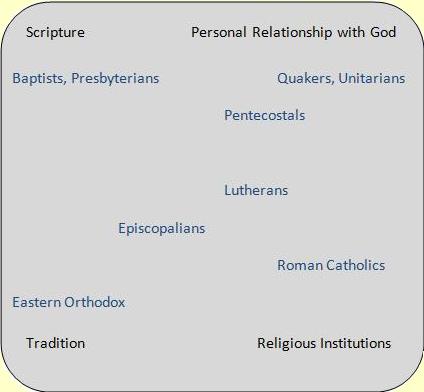

I think that in the Abrahamic faiths, guidance and inspiration come mainly from four sources:

- Scripture, understood as the written word of God, which may variously include the Pentateuch, the whole Hebrew Bible, both Christian testaments, or the Qur’an.

- A personal relationship with God, manifested in prayer and the inner voice of conscience.

- Tradition, understood as the ideas and actions of the historical community inspired by God.

- Religious institutions that provide guidance and doctrine today.

Almost all believers will acknowledge all four authorities, yet the weight that they give each one varies substantially. That variation is so important that I almost think one can classify denominations by how they weigh the four.

For example, the Reformation doctrine of sola scritura (by scripture alone) implies, first, that the Christian Old and New Testaments have a unique status as the perfect and complete word of God, and second, that one needs no other guidance. The Bible is not part of tradition: it is the sole basis of tradition. It is not produced by institutions: it creates them. It checks and inspires personal prayer. Hence the reading of scripture is the most important religious act.

In sharp contrast, Orthodox Christians believe that the Bible is one manifestation of the true (“orthodox”) religious tradition. The Bible is not fundamentally different from other fruits of tradition, such as the liturgy, the writings of the Fathers, the icons, and the shape and orientation of churches. St. Luke wrote the Gospel named after him, but he also painted the first portrait of Mary and Jesus, which is the model for subsequent icons. St. Basil was post-Biblical but he was inspired in the same way St. Luke was. The decision of a church synod is only valid if it is consistent with tradition and becomes traditional.

Meanwhile, Catholics take seriously the Bible, tradition, and personal devotion, but a defining characteristic of Catholicism is the belief that the institutionalized church (founded by Jesus and headed by St. Peter) is able to teach “magisterially,” changing tradition, reinterpreting scripture, and redirecting belief.

Near the fourth corner of the graph would be denominations like the Society of Friends, which strongly emphasize the personal, inner voice of prayer and conscience. Quakers pray collectively as well as individually, but any individual may be moved to speak. They read the Bible but also other works that are seen as inspired, including (at least nowadays) non-Christian writings.

These are all Christian examples, but I think a roughly similar analysis would work for Jews and Muslims.