- Facebook18

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 18

The left should represent the lower-income half of the population; the right should represent the top half. When that happens, the left will generally advocate government spending and regulation. Such policies may or may not be wise, but they can be changed if they fail and prove unpopular. Meanwhile, the right will advocate less government, which (again) may or may not be desirable but will not destroy the constitutional order. After all, limited government is a self-limiting political objective.

When the class-distribution turns upside down, the left will no longer advocate impressive social reforms, because its base will be privileged. And the right will no longer favor limited government, because tax cuts don’t help the poor much. The right will instead embrace government activism in the interests of traditional national, racial or religious hierarchies. The left will frustrate change, while the right–now eager to use the government for its objectives–will become genuinely dangerous.

This class inversion is evident in many wealthy democracies, although usually with exceptions and complexities. For instance, in the USA, Democrats now represent the 17 richest congressional districts and most of the richest 50. Put together, Democratic districts are wealthier than Republican ones, although Democratic candidates often win a bit more of the vote below $50,000/year than above that income level. It’s in this context that we now see Republicans eager to use state power against private companies on cultural issues.

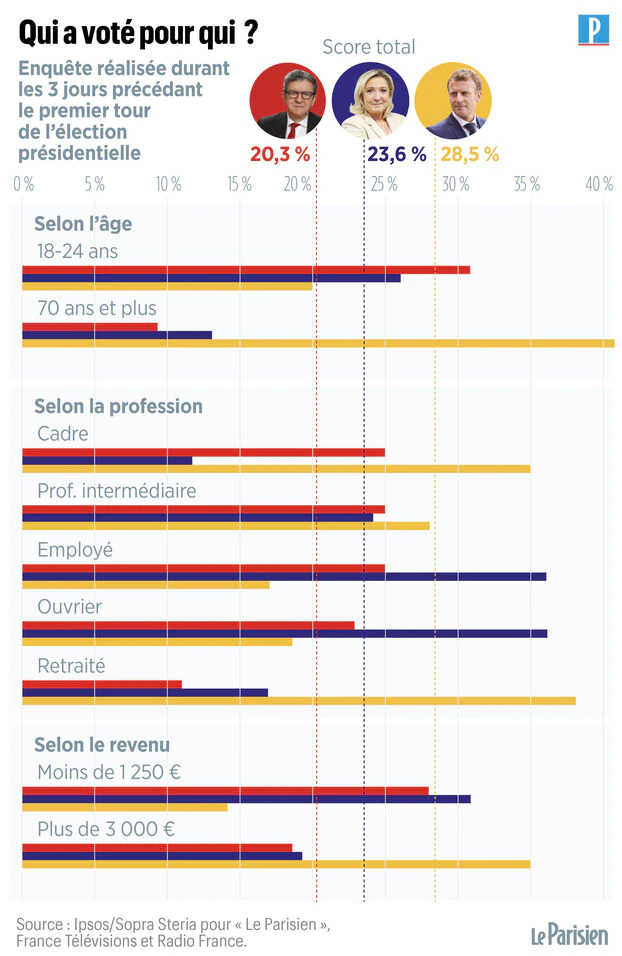

A similar inversion was evident in France this week. The class called “cadres” could be translated as executives, although I understand that it is a larger category than that English word implies. Among the cadres, Macron (a centrist technocrat) won and Melenchon* (from the left) came in second, with Le Pen (right-wing) drawing only about 12%.

The “intermediate professions” split their votes about evenly. This is a large and diverse group (26% of all employees), ranging from teachers to technicians. I would guess that sub-groups within this 26% voted quite differently from each other.

At the bottom of the scale–the ordinary employees and workers–Le Pen won by pretty substantial margins. Melenchon edged out Macron among these two categories, but he ran far behind Le Pen. If we look instead at wages, Macron performed better at the higher end, while Le Pen and Melenchon split the lower end about evenly. Macron won the most retirees and came in third amongst the young.

In the first round, French voters had numerous choices, and three candidates finished pretty close to even. That makes the outcome somewhat difficult to compare to a two-party contest between left and right, as in the USA. But one could envision Biden as a kind of hybrid of Macron and Melenchon (we can debate which one he is closer to), and Le Pen as Trump. Then the class inversion is clear.

This pattern is by no means exclusive to France, but it presents dangers wherever it appears.

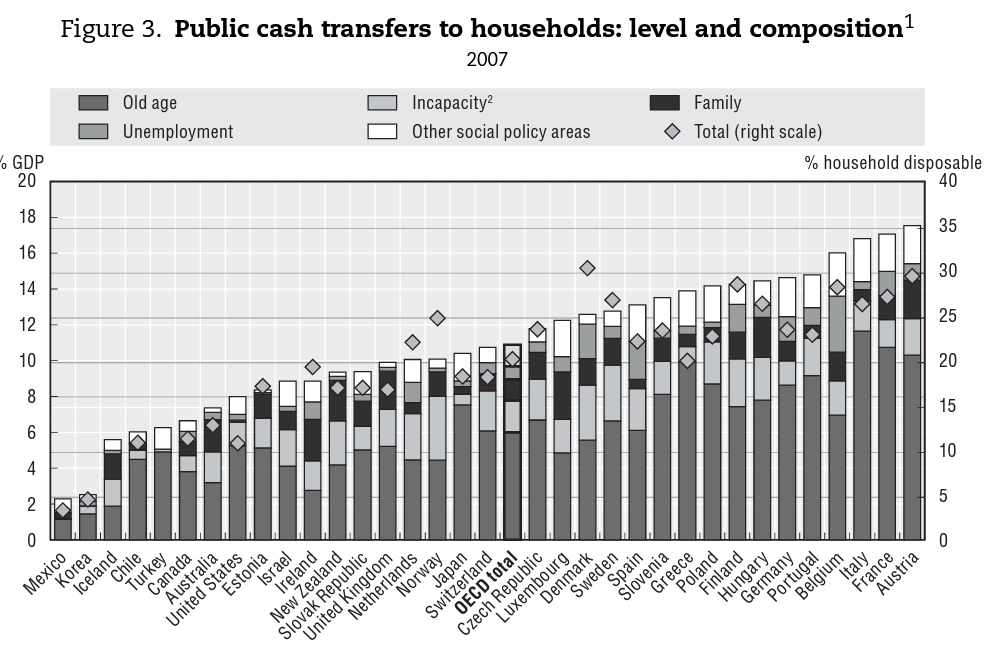

I do perceive France as combining relatively egalitarian economic policies with a particularly sharp gradient of prestige and power. As the figure below shows, France uses taxation and spending to transfer far more cash than the US does (albeit mostly to pensioners), yet an extraordinary proportion of French business, cultural, and political elites attend a few Parisian schools. This means that a welfare state that redistributes a great deal from rich to poor has a culturally elite look. That may be a refined version of an international problem.

*This blog isn’t letting me use accent marks, unfortunately. See also: the social class inversion as a threat to democracy; what does the European Green surge mean?; and why the white working class must organize