- Facebook102

- Twitter1

- Total 103

The Tufts University Prison Initiative of the Tisch College of Civic Life (TUPIT) is my institution’s contribution to the national movement for prison education. Colleges and universities are offering classes, degree programs, and special events for people in prisons or for incarcerated people along with students who come from “outside.” Sometimes, corrections staff and scholars of criminal justice also participate in these programs as learners, educators, or both.

In the era of mass incarceration–and in the wake of massive cuts to prison education programs–these efforts are far too small to fill the need, but they offer valuable opportunities and potential models for broader reform. Some of my favorite colleagues are deeply involved in prison education, and that includes the Founding Director of TUPIT, Prof. Hilary Binda, and her colleagues here at Tufts.

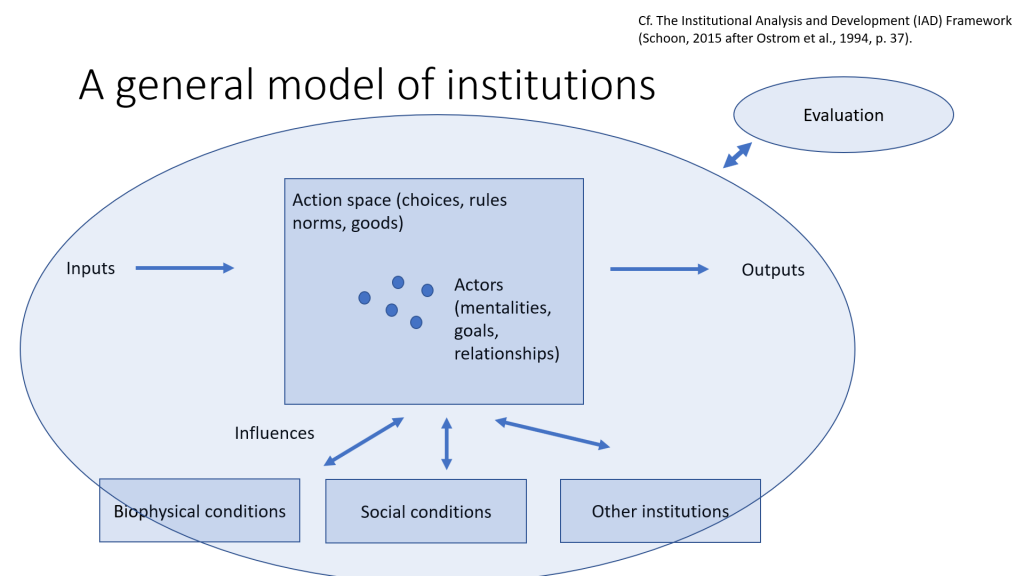

Thanks to TUPIT, I got to guest-teach a class at MCI-Concord last week. The class consisted of about 25 incarcerated men who are working on associates degrees. I presented my current working model for institutions, which I had also presented a few days earlier in the very different environment of a Tufts brown-bag series.

I told the students at MCI Concord that they should decide whether we’d focus on the prison as an institution, or spend more time on other examples. I’d say that we talked about prisons about half the time during the 2-hour conversation, but we also discussed families, gangs, schools, businesses, the foster-care system, and even biological systems such as forests. At least one student was interested in understanding the self as an “institution” that could fit the model. At Tufts, in contrast, the main institution that we’d discussed was “science”—mainly because that was the topic of the brown bag series in which I presented. Science and a prison make a pretty sharp contrast, but the model covers both.

For me, a goal was to test the validity of the model with this particular group. I think it largely passed muster, although many classes are too polite to share their reservations, and this was an exceptionally polite class, by any standard.

Certain aspects of the model seemed illuminating for at least some students. For example, the diagram shows a two-way arrow between biophysical conditions and the action space, which is composed of rules, norms, etc. Students at MCI-Concord generated the insight that the walls and barbed wire around the prison are biophysical conditions that both shape, and are shaped by, the rules and norms on the inside.

Among the interesting topics that arose was the distinction between a rule and a norm. Which is the right word for “Don’t snitch” within MCI-Concord? It is not an official rule; in fact, it violates the official rules. But it may be more than a norm, since it is enforced by the community, with clear consequences. Maybe it is a community-imposed rule.

I took one major challenge away from the conversation. The model that I presented is static or cross-sectional. It analyzes how an institution functions at a given time. The students wanted to know how people develop and change as they pass into, out of, and through multiple institutions. I suggested to them that they might be thinking that way because they’re taking a course that is all about personal transformation, but I also acknowledged that personal change is a concern for everyone, everywhere. So I came away feeling that the model of institutions should somehow connect to a model of personal development.

Finally, a word about the origins of this model. Where did I get this diagram, and why do I claim it might be valid? Essentially, it is my simplification of the Institutional Analysis and Design Model developed by Elinor Ostrom and her colleagues, which she presented in her Nobel Lecture. That is a pretty strong pedigree. I have simplified it in order to make it more general. The kinds of cases that Ostrom investigated are well modeled by game theory. They involve actors with fairly fixed goals who interact by bargaining. But human beings also interact in other kinds of situations, e.g., when we don’t know what we want and we are open to discussing it, or when our interests fuse due to very strong emotional attachments. My more general model is meant to cover bargaining situations, deliberative situations, loving relationships, and more. I am also interested in explicitly analyzing the role of power in institutions—not that Ostrom was blind to power, but I think she interpreted it too narrowly. I have claimed that power operates on every element of this model.