- Facebook81

- Twitter1

- Total 82

I’ve been in Madrid, Munich, and Berlin for a few days of vacation with family, plus the meetings with scholars from Spanish-speaking countries and scholars and activists from the former Soviet bloc that are described in “Civic Studies Goes Global” (July 17). In all, I had conversations with roughly one hundred people, if you include the high school students whom I taught in their school outside of Madrid, a firm of Spanish anarchist architects, grad students from countries like Belarus and Georgia, and even the well-informed guide who led our walking tour of Berlin’s Mitte. We also learned a lot from museum displays in places like the German Historical Museum, and I’m deep into David Blackbourn’s History of Germany 1780-1918: The Long Nineteenth Century.

Memory politics (how political actors influence what nations or other groups remember) is important everywhere and often generates current divisions. That is true in the United States, where questions of American exceptionalism versus the original sin of white supremacy are at the forefront right now. A leading question is how we should remember our past–not just what we should do next. Similar questions arise in the former Soviet bloc, in Latin America, and practically everywhere I can think of.

Germany does a good job with its memory politics today. The Federal Republic has made an acknowledgement of its Nazi past central to its civic culture–but you can see how that stance evolved, sometimes painfully, in the post-War era. In the library of an agricultural institution, I read a proclamation issued in 1945 on behalf of Bavarian farmers. It denounces the tyranny and war they have just experienced. The farmers express sympathy for the murdered, including an explicit mention of the death camps. But they add that it is “particularly” cruel that the tyranny conscripted Bavarian agricultural workers, since a farmer has Christian love for the land and other people. I admit that my first reaction was that these farmers were probably part of Hitler’s electoral base in 1932. That turns out not to be true–he did much better with Protestant rural voters and lost Bavaria (narrowly) to the Catholic Centre Party in the last free election of Weimar. Still, this document seems like only the first halting step toward an appropriate view of the past.

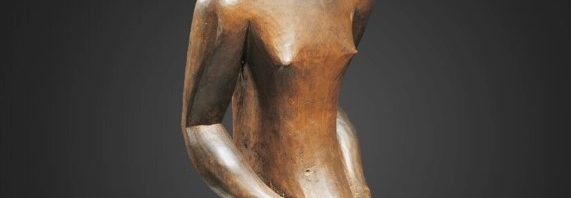

A fine example of current memory politics–German, but one could imagine similar efforts in other countries–is the exhibition “Beyond Compare: Art from Africa in the Bode-Museum.” Bronzes and other sculptural works from Africa are paired with European sculptures selected from this extraordinary collection. The labels invite us to ask why some things have been categorized as ethnographic objects and others as works of art; how to think about artists whose names are famous or who are anonymous; how aesthetics, faith, and functionality interrelate; how various cultures represent power, gender, and otherness; how these objects found their way to a museum on the Spree; and how sculptures from Europe and Africa have been cleaned and displayed (in this case, the parallels are more evident than the differences), among other questions.

As a whole, the Bode-Museum displays primarily Christian religious objects in a building that recalls a grand renaissance basilica, but its religion is High Culture or Geistesgeschichte, not Catholicism. Its contents are not of local provenance, nor looted from other countries, but purchased on the international market–albeit often as a result of someone else’s looting. And many of the objects are themselves efforts at memory politics, like this 19th-century figure of an ancestor from Hemba in the DRC.

See also: thoughts after a similar trip last year; the politics of The Sound of Music; the state of the classics in 2050; marginalizing odious views: a strategy; and civic education in the year of Trump: neutrality vs. civil courage.