- Facebook196

- Total 196

(Fishkill, NY) In an American Sociological Review article, Patrick Sharkey, Gerard Torrats-Espinosa, and Delaram Takyar find that “every 10 additional organizations focusing on crime and community life in a city with 100,000 residents leads to a 9 percent reduction in the murder rate, a 6 percent reduction in the violent crime rate, and a 4 percent reduction in the property crime rate.” This is not an iron law or conclusive finding, but it’s an impressive piece of social science. The authors use several methodological approaches to triangulate on the same basic finding: civic associations cut crime.

Incidentally, crime rates fell in major US cities just as the number of anti-crime civic groups rose. That doesn’t prove causality, any more than the decline of the European stork population is responsible for declining birth rates in Europe. But along with the causal evidence assembled by Sharkey et al., there really is a plausible case that a bottom-up, voluntary movement to make cities safer worked in the 1990s.

The evidence also suggests that it wasn’t mainly the explicit anti-crime groups that had the biggest effect. Substance-abuse and workforce-training organizations seem to be more important, although that finding is less secure than the general relationship between voluntary groups and safety.

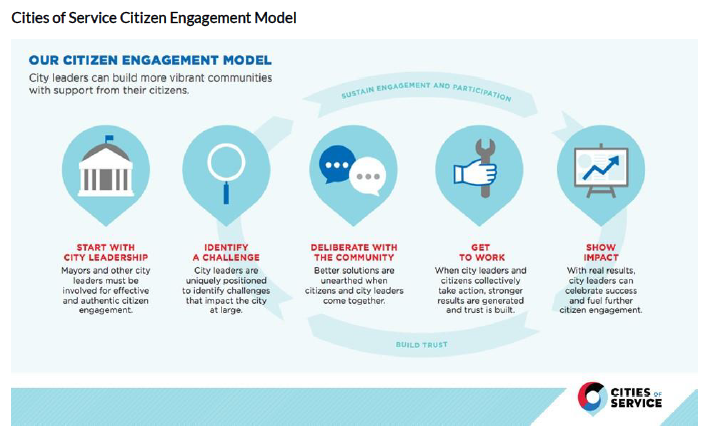

The question is how to get more citizens involved in the kinds of civic work that can make neighborhoods safer and otherwise better places to live. One opportunity is presented by all the citizens who step forward to give hours of service. Instead of being satisfied with low-impact volunteering efforts, we could help these citizens to organize themselves into powerful groups. And instead of letting them work in isolation, we could coordinate their efforts with those of city officials and agencies and local businesses to address common goals together.

That is the model of Cities of Service, about which Myung Lee and I wrote a Stanford Social Innovation Review article. One specific project of Cities of Service is Love Your Block, in which cities and neighborhood residents get resources to identify and work together to address local needs–the residents contributing free labor, and the city offering its support.

Last year, Mary Bogle, Leiha Edmonds, and Ruth Gourevitch of the Urban Institute wrote a qualitative evaluation of three Love Your Block projects–in Phoenix, Lansing, and Boston. Here are my Google Streetview pictures of the Phoenix and Boston projects, both of which are park renovations.

Bogle, Edmonds, and Gourevitch talked to active grassroots leaders involved in these projects and to other people in the same neighborhoods. They produced social network maps of old and new relationships among the people involved (as a way of measuring changes in social capital). They asked interviewees whether the projects had affected relationships, collective efficacy (the ability of a community to control its own environment), public ownership of public spaces, and safety.

Overall, the results were positive. Participants generally reported more and stronger working relationships. Everyone perceived that crime had declined, although they understandably cited many causes for that trend, not just Love Your Block. Relatively few of the interviewees who were not directly involved in the project saw evidence of stronger community ties, but they were more likely to see such value in Lansing than in the other two cities.

The contexts differ a lot. In Boston, the neighborhood is changing fast–pressures of gentrification are powerful. Some of the Boston participants are well connected to local elected officials and took advantage of that form of social capital. But horizontal ties in the Boston neighborhood are weaker. “A few participants thought community cohesion had gotten worse.” That would not be an effect of the park restoration but rather a consequence of rapid demographic shifts in the neighborhood.

In contrast, Lansing seems more stable, and more residents perceive more impact of Love Your Block on the community as a whole. Horizontal relationships are more important there.

In Boston and Phoenix, gentrification is a concern, and residents involved in improving their communities worry that their good work will displace residents. One Phoenix interviewee said, “I do have this anxiety about being so involved in the organizational side of things and also recognizing that any positive impact we have is veiled privilege.” That is not a problem in Lansing, where capital and population is at risk of flight. The Lansing team worked to restore a garden immediately adjacent to a public school that is vacant due to population-loss–not a problem in Boston.

Although local community work against a problem like crime is not likely to stop gentrification, it can mitigate some of its disruptive effects and empower residents so that they are able to negotiate somewhat better policies. In a 2016 report, HUD argued,

Although residential displacement is a primary concern of many changing neighborhoods, communities should also act to ensure that residents are not left alienated from neighborhood changes. … In order for low-income residents to garner the benefits of neighborhood change, communities should also pursue policy objectives further than affordable housing by supporting neighborhood organizations that foster greater connections between newcomers and long-time residents and that encourage civic engagement among all groups.

Similarly, my colleagues and I are studying the potential of an arts center in Boston’s Chinatown not to stop gentrification but to mitigate its damaging effects.

In the network diagrams of Love Your Block, local businesses emerge as important nodes, and “anchor institutions” (notably ASU in Phoenix and MSU in Lansing) are important assets. In Boston, these institutions are less important, and City Hall is more so. Interestingly, in Boston “the park is falling into modest disrepair already,” whereas Lansing’s park is “self-sustaining” thanks to active volunteer gardeners. That suggests that truly community-based networks are more valuable than ones that rely on official power. But it’s also easier to build horizontal networks in smaller places where the population is more stable and gentrification is much slower or nonexistent.

In July 2018, Cities of Service launched a new 10-city program focused on Legacy Cities (“older, industrial cities that have faced substantial population loss”). It will be evaluated by the Urban Institute.

Overall, the evidence seems strong that how communities organize themselves matters for reducing crime. Cities of Service Love Your Block program is one of the most ambitious and well-designed national efforts to engage communities. Early returns suggests that it may help cut crime. Although additional research and evaluation is appropriate (as always), the evidence already suggests that cities should use this approach to boosting public safety.

See also: can the arts mitigate the harms of gentrification? A project in Boston’s Chinatown; organizing is renewable energy; civic responses to Newtown and “the rise of urban citizenship