- Facebook96

- Total 96

When Democratic political candidates are asked about “youth,” often the first issue that comes to their minds is college affordability. For example, when Hillary Clinton was asked during a Democratic primary debate about how she would reach Millennials, her whole answer was about student debt.

I agree that student debt is a problem, but it’s not nearly as widespread as politicians assume. Nearly half of the debt is held by families in the top quartile, and for less advantaged younger Americans, student debt is only one of many challenges. Therefore, a much broader policy agenda is needed to engage the younger generation as a whole.

According to Harvard’s Institute of Politics, 42% of Millennials say that they or anyone else in their household holds student debt. Pew reports that 37% of 18-29s hold student debt in their own names. That is a lot of people, but not a majority.

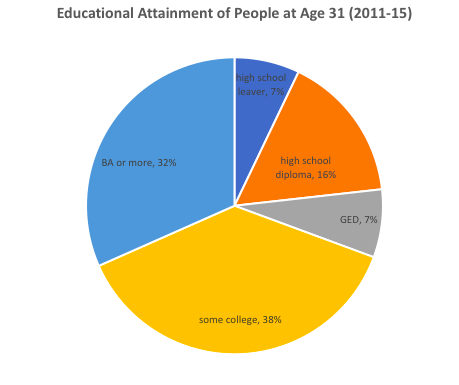

Forty percent of Millennials do not take any college courses at all (whether in community colleges or four-year institutions). They don’t have college debt, and their immediate economic problems may be quite different: the minimum wage, daycare, job training, GED options.

Another 38 percent enroll in college but don’t attain a BA. They have mixed experiences. Some of them incur debt but don’t hold degrees. However, according to Sandy Baum and Martha Johnson, 60% of graduates of public community colleges hold no student debt. They have Associates Degrees and are debt-free. Most of the people who borrow to obtain a 2-year degree attend for-profit institutions, and that’s a problem unto itself.

[Graph corrected on April 21]

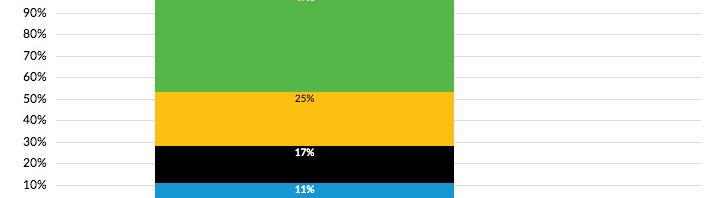

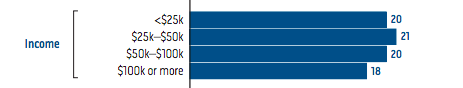

The proportions of all adults who report holding student debt is pretty steady across all income levels. (Source: Caroline Ratcliffe and Signe-Mary McKernan for the Urban Institute.)

But the loans get bigger as you go up the income ladder. Ratcliffe and McKernan report that people in the top quartile are least worried about their ability to repay their debt, yet they hold almost half of the dollars owed.

Similarly, Pew reports, “About two-thirds of young college graduates with student loans (65%) live in families earning at least $50,000, compared with 40% of those without a bachelor’s degree.”

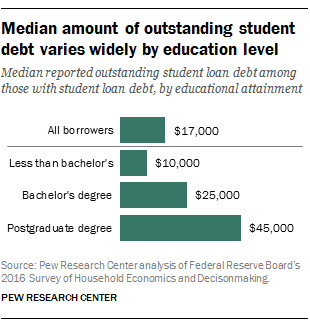

It should not be surprising that the more education you attain, the higher your debt. This also means that the people with the most debt are young adults in white-collar professions. They may be struggling, and I am fully sympathetic to them, but they represent the upper socio-economic stratum.

It would therefore be difficult to spend public money reducing debt without channeling most of the resources to upper-income young adults.

More youth regard debt as a problem than personally hold debt. Fifty-seven percent tell Pew that “student debt is a major problem for young people in the United States.” One reason may be that the prospect of debt deters people from pursuing college at all (or keeps them from pursuing more costly four-year and postgraduate degrees). In that case, college affordability and debt would be challenges for more than the 35%-40% of Millennials who actually hold debt.

But it’s a big assumption that the main reason people don’t pursue college degrees is the cost of tuition. About 41% of 31-year olds have no more than a high school diploma. The next step up the SES ladder for them would be an Associates Degree, and 60% of people who graduate from public community colleges have no debt. There may be many reasons 41% of young adults can’t get Associates Degrees–and they may not even want one–but tuition is not likely the main obstacle.

I’d be the last person to criticize reforms that make college more affordable. I just don’t think that this is the Rosetta Stone to the Millennial vote.