Elinor Ostrom was my favorite scholar. Her research was empirically rigorous and methodologically innovative. After working with Vincent Ostrom on water management, she turned to a series of studies of police. Her findings are pertinent today, when crime has fallen but we are (and should be) deeply concerned about racial bias in the criminal justice system.

The topic of policing scrambles ideological lines. Progressives who are otherwise favorable toward governments and unions get leery of police forces and police unions, for good reasons. Some conservatives who are normally concerned about limiting the state suddenly get enthusiastic about the police.

Placing Elinor Ostrom on an ideological map is also tricky. She was deeply influenced by works like James M. Buchanan’s and Gordon Tullock’s The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy, a foundational text of neoliberalism. She opposed centralized control and could be skeptical about redistribution, thus aligning with libertarians. At the same time, she was a committed environmentalist, a defender of indigenous cultures (many of which are not individualist or freedom-loving), and a theorist interested in moving “beyond markets and states”–the title of her Nobel lecture. She was a great proponent of commons and common-pool resources, which are popular on the left. To bring her ideas into the debate about policing offers insights that both sides may be prone to overlook.

Ostrom saw police as consumers and providers of a whole set of “services” (training, forensics, traffic control, patrol, arrests, pretrial detention, investigation, and more). Each unit within the world of policing–whether a forensic lab, a police station, or a specialized investigative team–negotiated with many other units to do its work. Some negotiations were formal, e.g., a town’s police department paying a different city’s forensic lab for services. More often, the negotiations within and among police systems were informal. Citizens were also organized in numerous overlapping ways–towns, counties, states, voluntary associations, juries–that influenced the police.

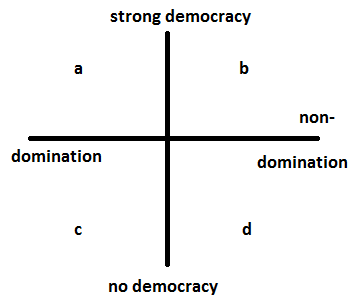

Ostrom analyzed all this complexity from the perspective of individuals, some of whom might happen to be police officers or other kinds of “professionals.” Citizens–meaning all individuals concerned with solving problems–would generally benefit if: 1) there were many potential providers of services, so that they had some choice, 2) the scale and boundaries of problems matched the scale and mandate of organizations, and 3) they could influence the goals and priorities of the police.

Her main empirical finding was that consolidating police departments reduced the quality of policing–as defined by citizens. Consolidation limited the choice available for services like training and forensics. It reduced the leverage that local police had over larger entities. It kept front-line professionals from being able to define goals and priorities, because they got slotted into larger systems. It kept them from addressing local problems (e.g., dangerous streets) because they had to meet targets, such as numbers of arrests, that came down from bureaucracies. And it blocked citizens in diverse communities from defining what “good policing” should mean.

Public safety (with a dimension of fairness to all) is a common-pool resource. Everyone benefits when it’s provided, but anyone can degrade it by illegally harming others; and lots of people must actively contribute to make it available. Lin Ostrom and her colleagues developed eight design principles that help with the management of common-pool resources, writ large. I list them below (from this summary) and offer some thoughts about how each applies to policing in the USA.

1. Define clear boundaries. Most police forces and organizations do have clearly defined jurisdictions. The fact that the geographical boundaries around police departments, sheriffs’ departments, state police, federal agencies, etc. form a complex pattern is probably an advantage, not a source of inefficiency or damaging conflict, according to the Ostroms’ “polycentric” theory. Thus our police systems do OK on this first design principle.

However, if we move beyond “clarity” and use other criteria to assess the boundaries, we see problems. For example, at the time of Michael Brown’s killing, the government and police force of Ferguson, MO were dominated by Whites even though the majority of the city was Black, and the metro area as a whole was better aligned with the Black population than the city was. To put it another way, the borders around Ferguson were unrelated to real patterns of settlement.

2. Match rules governing use of common goods to local needs and conditions. In the US, criminal justice works poorly by this standard. The laws governing citizens–and policies for the police–are set by state legislatures and Congress. Their decisions are not helpful in many specific contexts. For example, criminalizing drugs might have some benefits for reducing drug abuse, but it is harmful in the neighborhoods where drugs are sold.

3. Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules. Most Americans have a vote and free speech. But we exercise those forms of influence at inappropriate scales and within unhelpful boundaries. A citizen of Baltimore gets a vote in Maryland statewide elections but is outvoted by suburbanites. The police are more accountable to the city and the state than to the specific communities where they work.

4. Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities. Here again, mandates by state and federal authorities clearly interfere. In fact, community members are hardly involved at all in making rules in the domain of criminal justice. Common-pool resources rarely survive when this principle is violated.

5. Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behavior. We have police review boards and other tools for monitoring police. There are some interesting and valuable examples, like Community Policing in Chicago Beat Meetings. Still, my sense is that monitoring is underdeveloped.

6. Use graduated sanctions for rule violators. The general principle is that violations of rules should carry highly predictable costs, but the costs should start low. If punishment begins at a draconian level, not only may the perpetrator be unduly harmed, but the community is likely to excuse some violators entirely. A first-time offender should be able to pay the price and then be completely embraced by the community. Although penalties should start low, they should rise steadily with repeated infractions. For both law-breakers and police, this principle is almost uniformly ignored in American criminal justice.

7. Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution. In the context of criminal justice, that would mean helping citizens to resolve disputes without necessarily involving the police. It would also mean allowing citizens to resolve their disputes with the police without filing federal lawsuits. Both opportunities seem sorely lacking, despite important exceptions.

8. Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system. We do the opposite. Mandates flow down from states to cities to neighborhoods; and Congress influences the whole system without much accountability.

In short, criminal justice in the United States is a commons problem that we manage in ways that violate almost every principle for the management of common resources.

Because my concern is with racial injustice, I have no interest in marginalizing racial analysis of policing. However, it is important to structure institutions well. If we assume that the majority population is prone to treat minorities unfairly, that is an extra reason to design the rules right. We should also work on reducing racial bias, but we’d have to be awfully optimistic on that front not to give primary attention to institutions. The design principles are particularly important when we have good reason to mistrust some key actors.

I think restructuring criminal justice in line with common-pool management principles is a promising alternative to “abolition.” To be sure, we should ask the critical question, Why do we employ armed and uniformed paramilitary organizations to keep the domestic peace? The idea of abolishing police is worthy of debate. However, wholesale social transformation has a pretty poor record of success. Restructuring is a better place to start.

By the way, this approach is compatible with recognizing that American police serve many people in many communities very well. We needn’t reorganize everywhere, and we may be able to learn from the better examples.

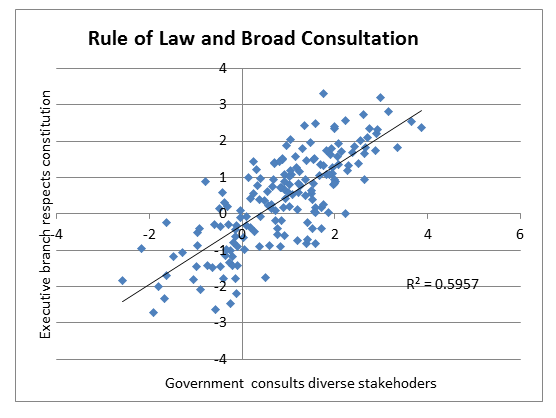

Finally, this approach has the great advantage of viewing public safety as the job of many actors, of which the police are only one. There is growing evidence that voluntary citizens’ efforts are important for reducing crime. In an American Sociological Review article, Sharkey, Torrats-Espinosa, and Takyar find that “every 10 additional organizations focusing on crime and community life in a city with 100,000 residents leads to a 9 percent reduction in the murder rate, a 6 percent reduction in the violent crime rate, and a 4 percent reduction in the property crime rate.” That finding fits very nicely with the Ostroms’ theory. Vincent Ostrom told my friend Paul Aligica:

We do not think of ‘government’ or ‘governance’ as something provided by states alone. Families, voluntary associations, villages, and other forms of human association all involve some form of self-government. Rather than looking only to states, we need to give much more attention to building the kinds of basic institutional structures that enable people to find ways of relating constructively to one another and of resolving problems in their daily lives.*

The problem with policing is that we have not built structures that allow people to relate constructively across lines of race (and class) in order to resolve the problems that they define as important.

*V. Ostrom to P. Aligica, 2003, in Vlad Tarko, Elinor Ostrom: An Intellectual Biography, p. 49. See also: Ostrom, Habermas, and Gandhi are all we need; Habermas, Ostrom, Gandhi (II) or this video that explores Ostrom along with other “Civic Studies” thinkers.