I was in Eau Claire, WI, on Sunday and honored to present to a large group of active citizens convened by a local Indivisible chapter and other parts of the #resistance. I offered five tools for thinking about political movements. My presentation went into somewhat more detail, but this is the gist.

First, the question for citizens is “What we should do?” — where “we” means a concrete group of people like the folks convened in a room in Eau Claire on Sunday.

The hard part is to avoid a shift into “What should be done?” or “How should things be?” Those questions evade responsibility. They are also excessively easy. Carbon should be taxed; Trump should resign. Those points may be correct but they don’t tell us what we should do.

Second, any functioning political group, network, or movement should combine deliberation, collaboration, and civic relationships. Deliberation means discussing what to do in diverse groups. That makes us wiser. Collaboration means actually getting work done together, coordinating voluntary action. And civic relationships are the reasons that people participate.

That framework is central to my book We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For, which I wrote while Barack Obama was president. I have considered whether this framework is obsolete when a man who threatens the republic occupies the White House. I still believe it applies. For one thing, people learn to value deliberative and collaborative styles of leadership by participating personally in decent groups. When only 28 percent of Americans report belonging to any group that is inclusive and accountable, no wonder many tolerate Trump’s style of leadership. Besides, every large-scale social movement, no matter how adversarial, needs deliberation, collaboration, and civic relationships to move forward. These are scarce but renewable sources of power.

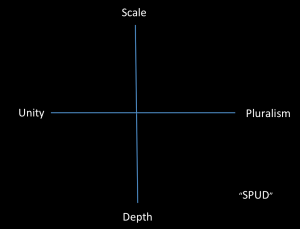

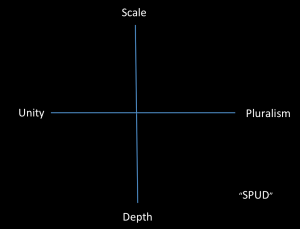

Third, try to maximize four goods that are often in tension. “Scale” means involving a lot of people. You can’t win without numbers. “Depth” means transforming people, building their skills, confidence, wisdom, and leadership. That’s necessary because we must all grow to be effective. “Pluralism” means encompassing a diversity of ideas and identities. Groups that fail to be pluralist get stupid and are unable to appeal to outsiders. “Unity” means coming together for one cause. Together they spell “SPUD,” which is a handy acronym. The challenge is that Depth trades off against Scale, and Pluralism against Unity. But the best movements achieve a bit of all four.

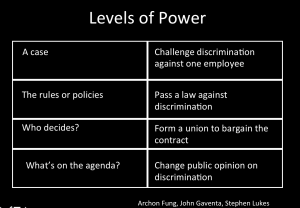

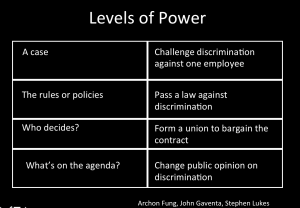

Fourth, work at several levels of power. The discussion of “faces” or “levels” of power goes back at least to Stephen Lukes and John Gaventa in the 1970s; I borrow from the recent version by Archon Fung. The basic idea is that you can challenge a particular wrong, or a rule or policy, or who makes the rules and policies, or what’s on the public’s agenda. For instance, you could help an individual vote, change voting laws, change who makes the voting laws (e.g., who draws district boundaries), or change how the public thinks about voting.

I venture the generalization that right-wing leaders are much better than the left at the third level of power. For example, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker has relentlessly attacked public sector unions (except police) so that union leaders can’t help determine policies; and he has passed restrictive voters to change who participates in elections. The left is better at the first and second levels of power, but those levels have limits.

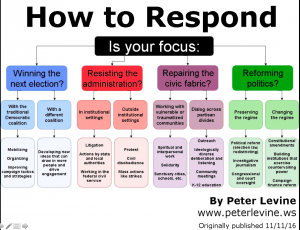

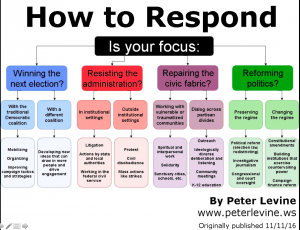

Finally, I reposted my “How to Respond?” chart, which I first released on this blog a couple of days after the November election. (Click to expand it.) It offers a set of strategies for activists in the current moment.

You can do more than one of these things. Probably some people should be doing each of them. But the eight options in the bottom row are too many for any one person or group to undertake, and they are in some tension. It’s hard for a group devoted to winning the 2018 election also to convene ideologically diverse conversations to bridge the gap between right and left. So most of us need to choose.

Note that I didn’t write, “How to respond to Trump’s victory.” This diagram doesn’t pretend to be nonpartisan or politically neutral. It offers options like winning the next election with a Democratic coalition and resisting the administration. But it is meant to be somewhat open-ended and subject to various interpretations. Genuine conservatives might take it to mean, “How to take our party back from a big-government chauvinist.” And leftists might interpret is as “How to respond to three centuries of injustice, in which Democrats are complicit.” As always, a plurality of views is an asset.

One way to use these tools might be to brainstorm concrete actions and then ask which cells in the last table you are filling, which levels of power you are addressing, how you are doing in SPUD, and whether you have deliberated and collaborated well. This process will not generate The Right Answer but it may help inform your strategies.