(Washington, DC) This is Arlie Russell Hochschild’s now-famous “deep story” of Louisiana Tea Party supporters, their “account of life as it feels to them.” It’s become famous because it’s also the “deep story” of at least some Trump voters:

You are patiently standing in the middle of a long line stretching toward the horizon, where the American Dream awaits. But as you wait, you see people cutting in line ahead of you. Many of these line-cutters are black—beneficiaries of affirmative action or welfare. Some are career-driven women pushing into jobs they never had before. Then you see immigrants, Mexicans, Somalis, the Syrian refugees yet to come. As you wait in this unmoving line, you’re being asked to feel sorry for them all. You have a good heart. But who is deciding who you should feel compassion for? Then you see President Barack Hussein Obama waving the line-cutters forward. He’s on their side. In fact, isn’t he a line-cutter too? How did this fatherless black guy pay for Harvard? As you wait your turn, Obama is using the money in your pocket to help the line-cutters. He and his liberal backers have removed the shame from taking. The government has become an instrument for redistributing your money to the undeserving. It’s not your government anymore; it’s theirs.

One response to anyone who holds this story is basically: Drop it. The people you believe have moved ahead of you on line are actually still behind, in the sense that they still face unfair disadvantages. For example, an applicant with an identical resume is much less likely to receive a job interview if his name sounds African American rather than White. (My own team is replicating this finding now, as part of a larger study to be released later.) To the extent that some people are moving forward on line, it’s because the most blatant inequalities are being to some extent remedied.

This is true, but I don’t believe it will work politically. I can’t think of any group in history that, upon being informed of its unfair advantages, has responded by yielding them willingly.* The standard response to being told you are privileged is to realize that you have something to defend. And I think that’s an especially likely response if you actually face hardships and disadvantages–which is true of White working-class rural Louisianans.

Waiting in line is a perfect example of a zero-sum situation. Literally, to move one space forward in a queue is to move everyone else one space back. As long as people see themselves in zero-sum relations with others, politics will be ugly. Of course, people don’t have to see the competition in racial terms. If, for instance, White rural Louisianans saw themselves as part of the same group as African-American rural Louisianans, they wouldn’t count successful Black people as winning against them. As Jamelle Bouie wrote yesterday, “many white Americans hold (and have held) a zero-sum view of politics, where gains and benefits for nonwhites are necessarily an imposition on their status.” He adds that how to “fix this white voter problem … is a separate and difficult question.” Telling the people whom Hochschild interviewed that they are racists does not seem to me a likely solution (nor does Bouie suggest it).

A different approach is to attack the zero-sum framing of the situation. People should be asking why anyone must wait so long for the American Dream. White Americans have voted for progressive policies when they have come to think that maybe everyone could achieve a good, secure, prosperous life. The underlying rules could be changed so that everyone wins.

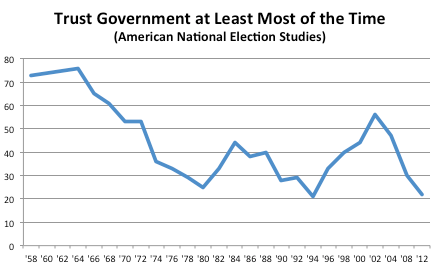

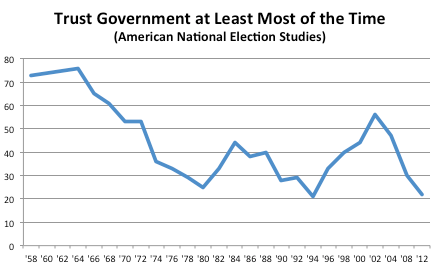

The immediate barrier to that kind of solution is distrust in government. If you don’t believe that government can be trusted to improve the social contract, then the existing contract may seem inevitable. Then your struggle with other people is zero-sum.

And people no longer trust the government much …

Perhaps the most common way to change this trend is to try to “sell” people on the government again– to persuade them that it offers solutions by outlining the policies that it can achieve and by using more effective rhetoric to defend it as an institution.

I dissent in part. People should not trust governments. As Jean Cohen writes, “One can only trust people, because only people can fulfill obligations.” Trust in the US government, as displayed by the American public ca. 1958, was naive. It often involved viewing presidents and other national leaders as friendly personalities, which reflected poor judgment. When it comes to governments and other large institutions, we ought to use one of these substitutes for trust:

- A sober assessment that the incentives are aligned to make the people who run the government also look out for our interests. I don’t think rural White Louisianans have much reason to make that assessment, even though, in my view, they would have been much better off with Clinton than with Trump.

- Personal connections to people who work in or closely with government. Because politics and government service are now the preserves of white-collar professionals, working-class people have few such connections. Consider, for example, the almost total absence of actual, current working-class people at both the Democratic and Republican National Conventions.

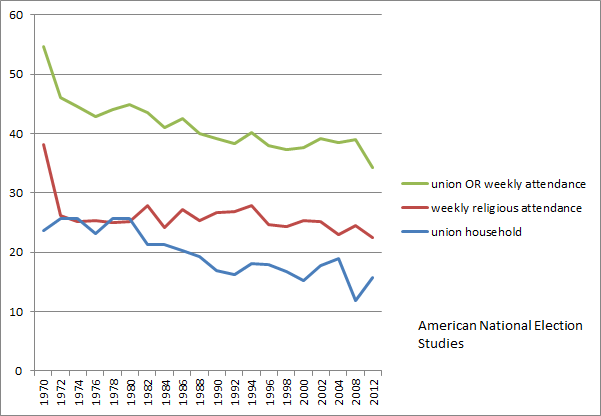

- Intermediary organizations that tangibly answer to us and (in turn) influence governments. Unions [and grassroots-based political parties] were prime examples, but they are shattered.

I’d support anything that makes White Americans less likely to see zero-sum situations in racial terms. But I believe it’s most promising to reduce the zero-sum situation more generally. Improving the social contract requires large institutions. Governments are strong candidates, although unions, co-ops, and other nongovernmental structures can be effective as well. Any large institution must, in turn, have direct, human connections to the people whose support it seeks. That means that even if the government is our main tool for social change, we need more than the state by itself; it must come with a panoply of social movements and organizations that link people to it. The hollowing out of these movements and organizations is thus at the root of our problems.

See also why the white working class must organize; to beat Trump, invest in organizing; building grassroots power in and beyond the election.

*Partial exception: the French nobility voted on August 4, 1789 to abolish the privileges of feudalism, spending all night eliminating one major privilege at a time by majority vote. It was a heady spectacle, but many of them lost their actual heads in 1793-4. Besides, they were voting for a new regime that promised all kinds of glories, not just moving themselves down the social hierarchy.