- Facebook580

- Total 580

I’m not sure what’s driving the traffic, but since yesterday, more than 2,500 people have visited my March 3, 2016 post entitled “why political science dismissed Trump and political theory predicted him.” I probably should revisit the topic now that the election is over (especially since I subsequently used standard empirical methods to predict a Clinton victory, thus acting like a political scientist instead of a political theorist).

Last March, I argued that mainstream–empirical or positivist–political science research on “American government” (as the specialty is called) has a vulnerability. Aiming to be a science, it uses data that can be amalgamated to produce models and predictions, such as data from modern US elections. The main method of prediction is to run trend lines from the past into the near future. Although normative assessment is always marginal in positivist social science, most of this research has an implied value-stance: our system works, it follows rules and norms, it’s fairly durable, the players are reasonably competent professionals who support the regime, and you should understand and respect it even you want to reform it. Any reform proposals should be informed by empirical evidence, because otherwise the reforms will have unintended consequences that are likely to be bad. As the great Theodore Lowi wrote, “Realistic political science is a rationalization of the present. The political scientist is not necessarily a defender of the status quo, but the result is too often the same, because those who are trying to describe reality tend to reaffirm it.”

In contrast, political theorists spend their time reading critical reflections on politics written in highly diverse and often tragic circumstances. Hannah Arendt’s writings from Nazi Europe and Frantz Fanon’s analysis of colonial Algeria are just two examples. Political theorists are quick to see that regimes can change, that they can be very bad, that they have debatable normative foundations, and that ideas can be revolutionary.

This means that when Trump arrived on the national scene, positivist political scientists were prone to think that he couldn’t get anywhere in our system–because no one like him had–and political theorists were ready to think that he might take over, because they spend their time considering tyrants, fragile regimes, and the power of xenophobia and authoritarianism. Although there were exceptions in both camps, I think these are reasonable generalizations.

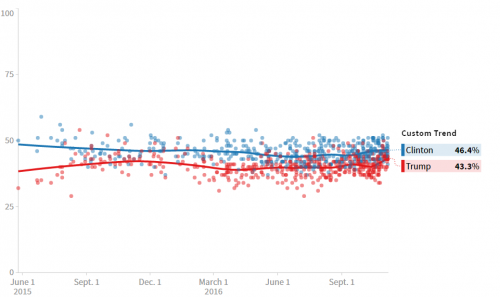

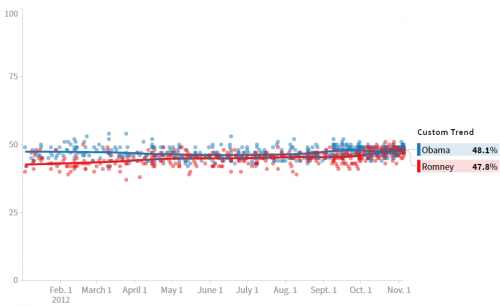

What should we conclude now that Trump is president-elect? It’s tempting to say that the theorists were right. But there’s actually a mainstream positivist account of what just happened. Presidential elections in two-party systems tend to settle at a point where each party has a 50% chance of winning. Given the way nominees are selected in multi-candidate primaries, a smallish faction can capture either party. Its nominee will still have very close to a 50% chance of winning: that’s why Trump got about half the votes, and because of the Electoral College, he won. Furthermore, given the constraints built into the regime as a whole, Trump is likely to govern as a Chamber of Commerce Republican rather than an authoritarian. And if he pushes too far, his party will lose the Congress in two years.

The trouble with political theory is that its predictions can be unmoored from empirical reality. Some political theorists have been predicting catastrophe or revolution throughout my lifetime. The fact that regimes sometimes change does not mean that ours is always about to. I think the odds are still against our regime changing fundamentally in the immediate future.

On the other hand, our political economy is problematic in ways that are not immediately evident from empirical data about the recent past. The Constitution does not fit the present society. The document has fundamental flaws, and the society is evolving toward oligarchy. Although empirical evidence is relevant to those claims, one needs a broader, deeper, and more evaluative stance on the regime as a whole to grasp a crisis such as our present one.