- Facebook64

- Total 64

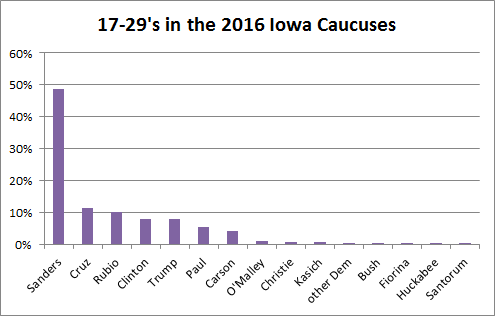

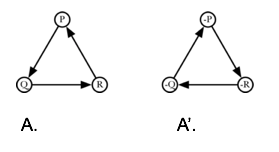

In “Coherentism via Graphs,”[i] Selim Berker begins to work out a theory of the coherence of a person’s beliefs in terms of its network properties. Consider these two diagrams (A and B) borrowed from his article, both of which depict the beliefs that an individual holds at a given time. If one beliefs supports another, they are linked with an arrow.

Both diagrams show an individual holding three connected and mutually consistent beliefs. Thus traditional methods of measuring coherence can’t differentiate between these two structures. However, Graph A is pretty obviously problematic. It involves an infinite regress—or what has been called, since ancient times, “circular reasoning.” Graph B is far more persuasive. If someone holds beliefs that are connected as in B, the result looks like a meaningfully coherent view. If you find coherence relevant to justification, then you will have a reason to think that the beliefs in B are justified—a reason that is absent in A.

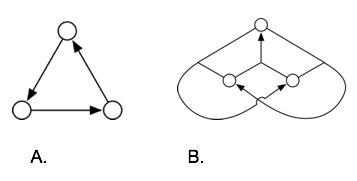

Berker also proposes a subtler but more decisive reason that B is better than A. Below I show A again, now with the component beliefs labeled as P, Q, and R. If the law of contraposition holds, than A implies another graph, A’, that is its exact opposite. A’ includes beliefs -P, -Q, and -R, and the arrows point in the reverse direction.

But that means that if belief P is justified because it is part of a coherent system of beliefs, then the same must be true of -P, which is absurd.[ii]

The overall point is that coherence is a property of the network structure of beliefs. That should be interesting to coherentists, who argue that what justifies any given belief just is its place in a coherent system. But it should also be interesting to foundationalists, who believe that some beliefs are justified independently of their relations to other ideas. Foundationalists still recognize that many, if not most, of our beliefs are justified by how they are connected to other beliefs. Thus, even though they believe in foundations, they still need an account of what makes a worldview coherent.

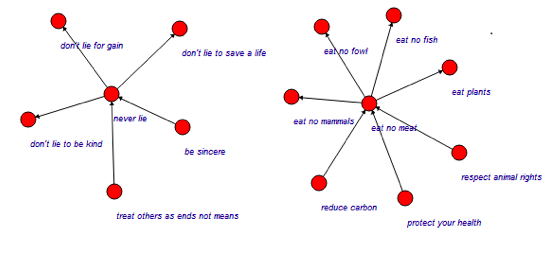

I have been developing a similar view, with a narrower application to moral thought (and without Berker’s deep grasp of current epistemology). I am motivated, first, by the sense that what makes a moral worldview impressively coherent cannot be seen without diagramming its whole structure. Imagine, for instance, a person who holds two major moral beliefs: “Never lie” and “Do not eat meat.” Assume that this person has not found or seen any particular connection between these two main ideas.

His or her set of maxims is perfectly consistent: there is no contradiction between any two nodes. And every idea has a connection to another. But if we wanted to judge the coherence of this worldview, we would not be satisfied with knowing the proportion of the components that were consistent and directly connected. It would matter that the person holds two separate clusters of ideas—two hubs with spokes. This person’s network is fairly coherent insofar as it is organized into clusters rather than being completely scattered; but it would be more coherent if the two clusters interconnected via large integrating ideas. You can’t see the problem without diagramming the structure.

I also have another motivation for wanting to explore moral worldviews and political ideologies as networks of beliefs. In moral philosophy and political theory, constructed systems are very prominent. Although diverse in many respects, such systems share the feature that they could be diagrammed neatly and parsimoniously. In utilitarianism, the principle of utility is the hub, and every valid moral judgment is a spoke. That theory is so simple that to diagram it would be trivial. Kantianism centers on several connected principles, and Aristotelian, Thomist, and Marxist views are perhaps more complicated still. But in every case, a network diagram of the theory would be organized and regular enough that the whole could be conveyed concisely in words.

In contrast, my own moral worldview has accumulated over nearly half century as I have taken aboard various moral ideas that I’ve found intuitive (or even compelling) and have noticed connections among them. My network is now very large and not terribly well organized. A narrative description of it would have to be lengthy and rambling. Many of my moral beliefs are nowhere near each other in a network that sprawls widely and clusters around many centers.

I suspect this condition is fairly typical. No doubt, individuals differ in how large, how complex, and how organized their moral worldviews have become, but a truly organized structure is rare. (I have asked a total of about 60 students and colleagues to diagram their own views, and only one of the 60 gave me a network that could be concisely summarized.) That means that such constructed systems as Kantianism and utilitarianism are remote from most people’s moral psychology.

Further, I think that having a loosely organized but large and connected network is a sign of moral maturity. It is a Good Thing. That is obviously a substantive moral judgment, not a self-evident proposition. It arises from a certain view of liberalism that would take me more than a blog post to elucidate. But the essential principle is that we ought to be responsive to other people’s moral experiences.

Berker includes experiences as well as beliefs in his network-diagrams of people’s worldviews.[iii] In science, it should not matter who has the experience. An experience of a natural phenomenon is supposed to be replicable; you, too, can climb the Leaning Tower and repeat Galileo’s experiment. But in the moral domain, experience is not replicable or subject-neutral in the same way. Since I am a man, I cannot experience having been a woman my whole life so far. Thus vicarious experiences are essential to moral development.

If we are responsive, we will accumulate sprawling and random-looking networks of moral beliefs as we interact with diverse other people. These networks can be usefully analyzed with the techniques developed for analyzing large biological and social networks. It will be illuminating to look for clusters and gaps and for nodes that are more central than average in the structure as a whole. The coherence of such a network is not a matter of the proportion of the beliefs that are consistent with each other. Its coherence can better be evaluated with the kinds of metrics we use to assess the size, connectedness, density, centralization, and clustering of the complex networks that accumulate in nature.

On the other hand, if someone adopts a moral view that could be diagrammed as a simple, organized structure, he has not been responsive to others so far and he will be hard pressed to incorporate their experiences in the future. At the extreme, his simple graph is a sign of fanaticism.

See also: envisioning morality as a network; it’s not just what you think, but how your thoughts are organized; Stanley Cavell: morality as one way of living well; and ethical reasoning as a scale-free network (my first thoughts along these lines, from 2009).

Notes

[i] Berker, S. (2015), Coherentism via Graphs. Philosophical Issues, 25: 322–352. doi: 10.1111/phis.12052

[ii] “Coherence, we have been assuming, is a matter of the structure of support among a subject’s beliefs, experiences, and other justificatorily-relevant mental states at a given time.” But we can use directed hypergraphs (in mathematics, networks in which any of the nodes can be connected to any number of the other nodes by means of arrows) to represent all of those support relations. That is, we use directed hypergraphs to represent all of the relations that have a bearing on coherence. It follows that coherence is itself expressible as a graph-theoretic property of our directed hypergraphs (p. 339).

[iii] “Many theorists hold that a subject’s perceptual experiences are justificatorily relevant (in these sense that they either partially or entirely make it the case that the subject is justified in believing something).”

Last week I

Last week I