- Facebook22

- Total 22

I am speaking next week on a panel about empathy:

“Generative Empathies” (Rabb Room, Lincoln Filene Hall, Tufts University, March 30, 12 pm) with …

- Amahl Bishara, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Tufts

- Doris Sommer, Ira Jewell Williams, Jr. Professor of Romance Languages and Literature and Director, Cultural Agents Initiative, Harvard University

- Peter Levine, Associate Dean for Research, Tisch College

I don’t know quite what to say yet, but I am inclined to raise the following points.

First, for a very long time, writers have argued that sad stories generate empathy and improve the character. From his dismal exile on the shore of the Black Sea, the poet Ovid addresses a soldier friend in these lines:

Is it true? When you heard of my misfortune

From a distant land, was your heart sad?

You can hide and shrink to say it, Graecinus,

But if I know you well, it was sad.

Revolting cruelty does not fit your type,

And even less your avocation. For

The liberal arts, your highest concern,

Soften the chest so that harshness escapes.

— Ex Ponto, 1.6 (my trans.)

Ovid presumes that his story will soften the gruff Roman’s heart, especially because it comes in the form of a poem and the soldier is a devotee of the artes ingenuae: the liberal arts, or literally, the freeborn arts. The poem will work because the reader has been habituated by many previous poems to dislike cruelty. Apparently, “ingenuae” has aristocratic connotations, and so Ovid’s phrase for the “liberal arts” implies a higher class of people who have been civilized or humanized by the arts.

Here is another classic source for the idea that writing generates empathy:

- And early in the morning, he came again into the temple, and all the people came unto him; and he sat down, and taught them.

- And the scribes and Pharisees brought unto him a woman taken in adultery; and when they had set her in the midst,

- They say [sic] unto him, Master, this woman was taken in adultery, in the very act.

- Now Moses in the law commanded us, that such should be stoned: but what sayest thou?

- This they said, tempting him, that they might have to accuse him. But Jesus stooped down, and with his finger wrote [or drew] on the ground.

- So when they continued asking him, he lifted himself up, and said unto them, He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.

- And again he stooped down, and wrote [not drew] on the ground.

- And they which heard it, being convicted by their own conscience, went out one by one, beginning at the eldest, even unto the last: and Jesus was left alone, and the woman standing in the midst.

- When Jesus had lifted up himself, and saw none but the woman, he said unto her, Woman, where are those thine accusers? Hath no man condemned thee?

- She said, No man, Lord. And Jesus said unto her, Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more (John, 8:2?11)

What was Jesus writing? One answer: something concrete about the specific Woman, which made the scribes and Pharisees think about her (and about themselves) instead of applying the abstract law.

For centuries in the English-speaking world, to enter the ranks of the civilized and humane meant reading Shakespeare. One possible reason: Shakespeare’s special capacity for empathy, which is related to his refusal to push arguments of his own. Keats found in Shakespeare the quality that he called “Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Other critics have noted Shakespeare’s remarkable ability not to speak on his own behalf, from his own perspective, or in support of his own positions. Coleridge called this skill “myriad-mindedness,” and Matthew Arnold said that Shakespeare was “free from our questions.” Hazlitt said that the “striking peculiarity of [Shakespeare’s] mind was its generic quality, its power of communication with all other minds–so that it contained a universe of feeling within itself, and had no one peculiar bias, or exclusive excellence more than another. He was just like any other man, but that he was like all other men.”

So we have a model of the humane and sensitive educated person as one who has been habituated by the reading of moving stories to be empathetic and thus to show mercy or otherwise depart from harsh decisions.

This model conflicts with the idea that a just person knows the truth and obeys the consequences. St. Augustine recalls his sinful younger self enjoying the theater, where he was “forced to learn I don’t know what wanderings of Aeneas, oblivious to my own, and to lament the dead Dido, because she killed herself for love, while meanwhile with dry eyes I endured my miserable self dying among these things before you, God, my life. … In the theaters I took pleasure along with the lovers when they used each other for vice, even though their behavior was just the imaginary sport of a play, and when they parted I was sad along with them, as if I were really compassionate; yet I enjoyed both parts.” At the moment of his conversion, Augustine hears a voice saying, “take up and read, take up and read.” He understands this as a command to open the Bible at random. The first words he finds are those of Paul: “But put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh, to fulfil the lusts thereof” [Rom. 13:13?14]. Augustine recalls: “I wanted to read no further, nor was there need” (Conf., 1.13.20; Conf. 3.2.3.; Conf., 8.12.29).

This is a model of the just person as one who is unmoved by inappropriate empathy and who avoids reading texts that might make him sympathize with sin. Although he is a very different kind of person from Augustine, Judge Richard A. Posner writes in “Against Ethical Criticism” that “empathy is amoral.”

Imaginative literature can engender in its readers emotional responses to experiences that they have not had. We read King Lear and feel how–or some approximation to how–a failing king feels, the wicked bastard feels, the evil daughters, the good daughter, the blinded earl, the faithful retainer, the corrupt retainer, the fool, all feel. We experience simulacra of the agony of madness and the pang of early death in Hamlet, the depths of mutual misunderstanding in The Secret Agent, the loneliness of command in Billy Budd, the triumph of the will in Yeats’s late poetry. This is the empathy-inducing role of literature of which [Hilary] Putnam and [Martha] Nussbaum speak. But empathy is amoral. The mind that you work your way into, learning to see the world from its perspective, may be the mind of a Meursault [from The Stranger], an Edmund [from Lear], a Lafcadio [the lion?], a Macbeth, a Tamerlane, a torturer, a sadist, even a Hitler (Richard Hughes’s The Fox in the Attic).

Empathy can even undermine justice. It can make the empathetic person feel more virtuous without doing anything, and it can even strengthen his position in a conflict by making him look better to third parties. This can be true of sincere empathy. I believe, for instance, that the median Israeli voter has achieved some empathy for Palestinians, and that feeling both blunts the urgency of justice and makes Israel look better than it should in the eyes of the world. Note the applause in this speech by Barack Obama in Jerusalem on March 21, 2013:

I — I’m going off script here for a second, but before I — before I came here, I — I met with a — a group of young Palestinians from the age of 15 to 22. And talking to them, they weren’t that different from my daughters. They weren’t that different from your daughters or sons.

I honestly believe that if — if any Israeli parent sat down with those kids, they’d say, I want these kids to succeed. (Applause.) I want them to prosper. I want them to have opportunities just like my kids do. (Applause.) I believe that’s what Israeli parents would want for these kids if they had a chance to listen to them and talk to them. (Cheers, applause.) I believe that. (Cheers, applause.)

In sum: I don’t think empathy will suffice on its own. It must be connected somehow with justice and with actually taking just action. If you favor systematic moral theories, than you may recommend using one or more general moral premises that distinguish good empathy from bad empathy. A feeling of empathy will not be a reliable guide to right action, only an urge that you must critically assess in other terms.

If, like me, you are skeptical about organized moral theories and believe that empathetic responses can convey truths about the world, then you will view an empathetic response as a valid source of guidance. But not as the only kind of valid input: relatively abstract and impersonal considerations must also apply.

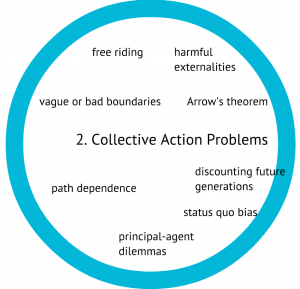

Academics certainly study these problems. Google Scholar finds more than 77,000 books or articles on free-riding, which is one variety of a collective action problem. It finds more than 9,000 citations of implicit bias, which I would categorize as a discourse problem. There is no shortage of material to read, and much of it is useful.

Academics certainly study these problems. Google Scholar finds more than 77,000 books or articles on free-riding, which is one variety of a collective action problem. It finds more than 9,000 citations of implicit bias, which I would categorize as a discourse problem. There is no shortage of material to read, and much of it is useful. limitations that we should address:

limitations that we should address: