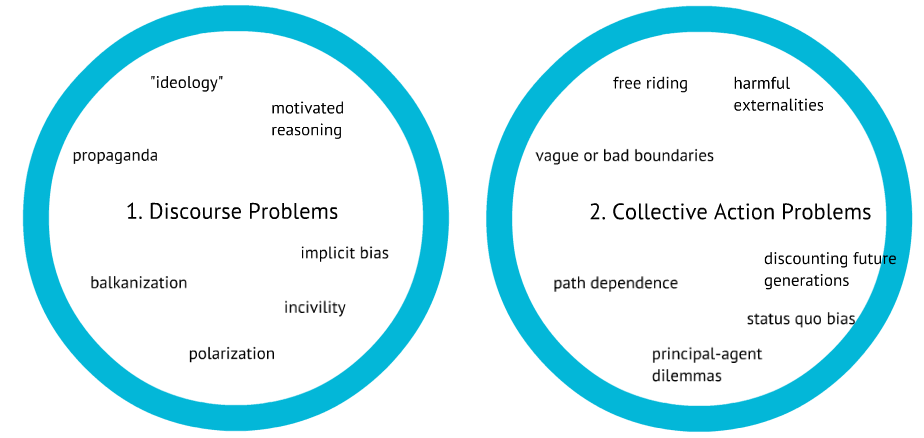

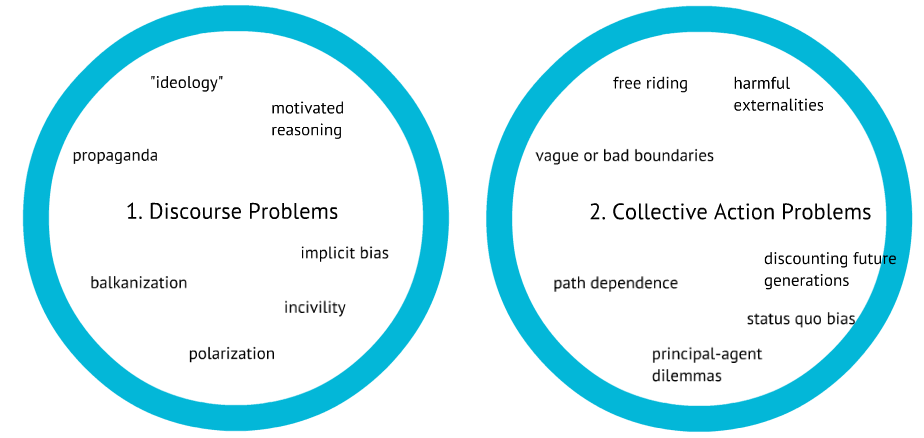

Human beings face two fundamental categories of problems: problems of discourse and problems of collective action.

Problems of discourse make our conversations go badly, so that we believe or desire the wrong things. They include, for example, our unconscious biases in favor of members of our members of our own groups and our strong tendency to “motivated reasoning,” or picking facts and theories because they yield the results we want. A different example is ideology, defined (in this context) as holding a distorted view of reality that preserves the advantages of the privileged.

Meanwhile, problems of collective action cause us to get results that we do not desire, even when we agree about goals and values. An example is the temptation to “free ride” on other people’s contributions, or the extreme cost of changing a system once it has been chosen and developed (“path dependence”).

How can I justify the claim that these are the two fundamental categories of problems? My claim is subjective, but it does arise from 20 years of thinking about social problems, during which I have constantly found myself drawn to two quite different conversations. One is about deliberation, communication, and the flaws thereof. The most relevant disciplines are political philosophy, cultural studies, and communications. Famous authorities include Marx and the Frankfurt School, Habermas, Derrick Bell, John Rawls, Judith Butler, and many more. The other conversation is about rational choice, public choice, and game theory. The most relevant disciplines are economics and social psychology. Authorities include Elinor Ostrom, James M. Buchanan, Mancur Olson, and Kahneman & Tversky.

The two sets of problems are connected. For instance, one explanation of motivated reasoning is that to choose the most convenient facts is easier than giving all the evidence a full and rigorous consideration; and we can get away with the easier path because we can free-ride on other people’s intellectual labor. Thus the discourse problem of motivated reasoning is linked to a basic collective action problem.

Yet neither set of problems is, in my view, reducible to the other. For instance, a very ambitious game theorist might assume that game-like models can explain all breakdowns of human interaction. But game theory takes as given the values and identities of the players. In fact, those are not fixed but are generated and changed by discourse.

By the same token, some cultural critics might argue that all of our problems arise from distorted discourse, bias, and ideology. But I think that even if we all sincerely agreed about something as important as climate change, problems of collective action would still be formidable. We would not only face the mother of all tragedies-of-the-commons but also challenges of path dependence (e.g., our dependence on internal combustion engines) and boundary issues (the countries that use the most carbon are separated from the big producers).

I am well aware that we also face a whole range of urgent concrete problems not shown above, such as global warming or racism today–or (at other times in our history) plagues and famines and invading hordes. But while those threats are matters of life and death for specific communities, the two categories shown above apply at all times. They establish the form of human interaction, into which are poured such specific content as poverty, racism, authoritarianism, disease, etc.

I was trying to think of a place where demographic diversity would be absent and where there would be such a high degree of consensus about one transcendent goal that the participants would not care about matters like poverty or climate change. In such a place, we might see neither discourse problems nor collective action problems. I came up with the all-male Orthodox Holy Community of Mount Athos, which is now a quasi-autonomous monastic republic within the EU. Although I certainly do not know the details, I quickly found an example of the two generic problems afflicting this community:

In June 1913, a small Russian fleet, consisting of the gunboat Donets and the transport ships Tsar and Kherson, delivered the archbishop of Vologda, and a number of troops to Mount Athos to intervene in the theological controversy over imiaslavie [the belief that the Name of God is God].

The archbishop held talks with the imiaslavtsy and tried to make them change their beliefs voluntarily, but was unsuccessful. On 31 July 1913, the troops stormed the St. Panteleimon Monastery. Although the monks were not armed and did not actively resist, the troops showed very heavy-handed tactics. After the storming of St. Panteleimon Monastery, the monks from the Andreevsky Skete (Skiti Agiou Andrea) surrendered voluntarily. The military transport Kherson was converted into a prison ship and more than a thousand imiaslavtsy monks were sent to Odessa where they were excommunicated and dispersed throughout Russia.

If a bunch of white men who have voluntarily renounced property, sex, and freedom and who are totally devoted to the Orthodox faith can face deadly problems of discourse and collective action, then these challenges seem universal. That doesn’t mean they always defeat us; it just means we always have to work on them.