- Facebook218

- Twitter1

- Total 219

The strongest arguments for the humanities are not about their effects. In order to decide whether any given outcome or impact is desirable, we must have a considered opinion of what is good. The humanities are the disciplines that address that question. We do not consider matters of value because doing so has good results; we do it to decide which results are good. So I have argued in a set of books and articles, the latest of which is Reforming the Humanities.

At the same time, however, the humanities are real practices and activities, taking time, costing money, and engaging people in the world. They exist in colleges and universities and also in k-12 schools and in a wide variety of community settings: book clubs, historical associations, museums, and the like. Participating in those activities and organizations will have effects, and it is worth studying them. The National Endowment for the Humanities does not conduct or support much empirical research on the humanities, and the whole topic is little studied. Yet the public humanities have reached substantial scale. As Elizabeth Lynn has written, “There are now 56 state humanities councils [that] receive more than one-third of all NEH program funds (over $40 million in FY2011) and they raise almost as many dollars in state and private funds. Each year they conduct many thousands of programs nation wide, providing what former NEH Chairman Jim Leach has called the ‘finest outreach education in the humanities in the world today.’”

As a contribution to the empirical research on the humanities, CIRCLE was very pleased to collaborate with Indiana Humanities on a study of the public humanities in the Hoosier State, as part of a national effort called “Humanities at the Crossroads.”

CIRCLE studies civic engagement, and the humanities do not overlap perfectly with civic activity. If we apply the ancient distinction between the active and the contemplative life, civic engagement is active, and sometimes the humanities are contemplative. Nevertheless, we saw a study of the humanities as relevant to our civic mission for two main reasons.

First, the public humanities give explicit attention to questions of ethics and values. That means they play an essential role in our civil society. As one participant in our study said, “I think that people appreciate the opportunity to come together and discuss pertinent topics. I do believe they see these activities as enrichment and community building opportunities.”

Second, people and organizations involved with the humanities form a network. Civil society is not just a list of separate organizations; the whole is (or should be) greater than the sum of its parts. Our study with Indiana Humanities was an opportunity to assess the whole network of public humanities organizations in one state, as a model for further research on the humanities and on other aspects of civic engagement.

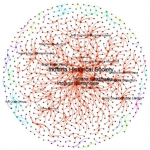

Because we took a network approach, we were able to reveal practically significant findings that would have been invisible otherwise. For example, we did not detect a statewide network organized around the humanities per se. As the small graphic to the left suggests, historical associations were more prominent and central. Although history is certainly one of the humanities, the lack of a network for the humanities (as a whole) presents challenges. For example, it makes it harder to connect the community-based humanities to universities, where literature is a much larger field than history. And it means that there is no coherent public voice for the humanities when they come under threat.

Because we took a network approach, we were able to reveal practically significant findings that would have been invisible otherwise. For example, we did not detect a statewide network organized around the humanities per se. As the small graphic to the left suggests, historical associations were more prominent and central. Although history is certainly one of the humanities, the lack of a network for the humanities (as a whole) presents challenges. For example, it makes it harder to connect the community-based humanities to universities, where literature is a much larger field than history. And it means that there is no coherent public voice for the humanities when they come under threat.

On the other hand, we found a large number of people and organizations concerned with the humanities in Indiana. By surveying an original sample known to Indiana Humanities and asking respondents to name others with whom they work, we found 2,147 individuals thought to be involved in the humanities within the state. Of those, 390 gave us data on their own activities. They told us that the humanities are as popular as or even more popular than in the past and that their activities contribute to the “sense of place” that every community wants to enhance. We also found that humanities organizations in Indiana are lean and longstanding. More than 20 percent have been in existence for a century or more, but funding sources for the humanities are flat or in decline.

These and many other findings are presented in Felicia M. Sullivan, Nancy N. Conner, Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, Peter Levine and Elizabeth Lynn, “Humanities at the Crossroads: An Indiana Case Study” (CIRCLE, in collaboration with Indiana Humanities, 2014).