(Washington, DC) This post–cross-posted on the Democracy Fund blog—is the third in a series about CIRCLE’s evaluations of the Fund’s initiatives to inform and engage voters during the 2012 election. These posts discuss issues of general interest that emerged from our specific evaluations. The previous entries in the series are: “Educating Voters in a Time of Political Polarization” and “Supporting a Beleaguered News Industry.” Join CIRCLE for discussion of the posts using the hashtag #ChangeTheDialogue, as well as a live chat on Tuesday, June 25th at 2pm ET/1pm CT/11am PT.

Since 2012, the Democracy Fund has invested in projects and experiments intended to inform and engage voters. Several of these efforts sought to change the way citizens respond to divisive and deceptive rhetoric. To succeed, an organization would have to (1) create an experience that altered people’s skills, attitudes, and/or habits, and (2) reach a mass audience.

In this post we focus on the second issue: scale. Since adults cannot be compelled to undergo civic education, and about 241 million Americans were eligible to vote in 2012, engaging citizens in sufficient numbers to improve a national election is challenging. Democracy Fund grantees used at least four different strategies to reach mass audiences with nonpartisan education.

First, the Healthy Democracy Fund’s Citizens Initiative Reviews convened representative groups of citizens to deliberate about pending state ballot initiatives in Oregon. The citizens’ panels wrote summaries of these ballot initiatives that the state then mailed to all voters as part of the Oregon voter guide. Although only 48 people were directly involved in the deliberations, the results of their discussions reached hundreds of thousands of Oregon voters. Penn State Professor John Gastil found that nearly half of Oregon voters were aware of the statements that these deliberators had written and that a significant portion of the voting public found the statements to be useful. In an experiment that Gastil conducted, citizens who read the statements shifted their views substantially and showed evidence of learning. So, in this case, a small-scale exercise in deliberative democracy led to mass public education.

Second, Flackcheck.org produced videos ridiculing deceptive campaign ads. The videos were free, online, and meant to be funny. A major reason to use parody and humor was to increase the odds that viewers would voluntarily share the videos with their friends and relatives. We asked a representative sample of Americans what would generally encourage them to share a political video, and 39% said that they would be more likely to share it if it was funny. The only attribute that attracted more support was the importance of the topic. We also asked respondents to watch one of three Flackcheck parody videos, and 37% thought the one they saw was funny, although 20% did not.

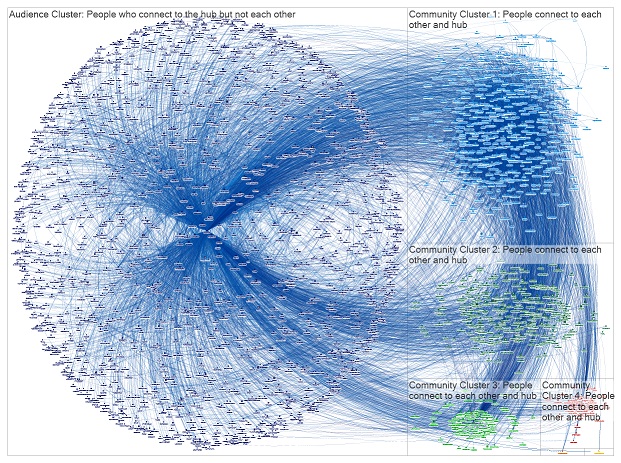

In the end, the Flackcheck parody videos attracted some 800,000 views. That is a relatively large number, although a small proportion of the electorate. On a subcontract from CIRCLE, Marc Smith is analyzing the dissemination network created by the sharing of Flackcheck videos online. Below are shown the people and organizations that follow Flackcheck’s Twitter account and their mutual connections. It is a substantial online community.

Third, AmericaSpeaks recruited individuals to deliberate online as part of Face the Facts USA. AmericaSpeaks is best known for large, face-to-face deliberative events called 21st Century Town meetings. Although they convene thousands of people, often in conference centers, their scale is small compared to the national population. The Face the Facts project provided an opportunity for AmericaSpeaks to recruit participants to low-cost and scalable Google Hangout discussions. That is a model that could be replicated as an alternative or a complement to more expensive, face-to-face discussions.

Finally, several projects involved influencing professional journalists or media outlets as an indirect means of educating the public. These projects took advantage of the fact that millions of Americans still receive information and commentary from news media sources. The Democracy Fund grantees strove to improve the quality of their coverage and thereby reach a substantial portion of the voting public.

The Columbia Journalism Review’s “Swing States Project” attempted to improve the quality of local media coverage by commissioning local media critics to critique the coverage . We interviewed political journalists in the targeted states. Among respondents who were aware of the project, 59% responded that it had influenced them. Thirty-six percent indicated that it had a moderate influence or influenced them “very much.” Although we cannot estimate how this influence on journalists affected voters’ understanding of the issues, the findings suggest that a fair number of journalists whose work is being read and watched by voters in swing states were taking steps to improve their coverage.

The Center for Public Integrity’s “Consider the Source” provided in-depth reporting on campaign finance issues that newspapers, broadcasters, and other news sources could use. CIRCLE interviewed 13 prominent experts who report on money and politics. Nearly half of these interviewees felt that CPI resources had influenced the conversation among media professionals, and that consequently the media now offers more comprehensive stories about money in politics. Although only 200,000 people read the CPI stories at the CPI website, the organization’s media tracking service estimated that the stories reached a potential circulation of 48 million people through pick up by other media organizations.

Although CIRCLE’s evaluations did not yield recipes for changing mass behavior, the following conclusions are consistent with our findings:

- Distributing recommendations from a credible public deliberation can have significant influence on the public, if the deliberation is reflected in an official vehicle, such as a state voter guide.

- “Providing resources to the media can be an effective means of reaching scale, if the source is viewed as fair and providing them with relevant and valued content

- It’s hard to get to scale by trying to become a destination site.