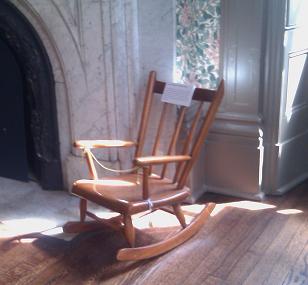

This is the tiny rocking chair in which Jane Addams learned to read as a little girl, encouraged by her father, John (“double-D”) Addams, who served in the Illinois State Legislature with Abraham Lincoln.

This is the tiny rocking chair in which Jane Addams learned to read as a little girl, encouraged by her father, John (“double-D”) Addams, who served in the Illinois State Legislature with Abraham Lincoln.

Zoom out to Jane Addams’ bedroom, decorated with a painted portrait of Tolstoy and wallpaper in the William Morris style. That room is at the head of the stairs in the gracious Italianate Victorian building known as Hull-House where Addams lived for many years.

Zoom further out to the neighborhood where once the Hull-House Settlement, a whole complex of public buildings around green courtyards, once served its neighborhood of tenement houses, factories, and outdoor food markets. “Served” is not really the right word, because the neighbors co-created Hull-House and all of its programs with Addams. Their neighborhood was flattened–quite literally–in the 1960s to make room for the spare modernist blocks of the University of Illonois at Chicago.

Addams always kept her distance from universities. It is an irony that UIC was built on the bulldozed buildings of Hull-House, after the latter had taken its unseccessful fight to survive all the way to the US Supreme Court. But today UIC is a diverse, engaged, urban research university–not much like the University of Chicago from which Addams kept a critical distance. So perhaps the irony is not so painful.

Zoom further out to follow my taxi en route from Addams’ house to Midway Airport. Soon we pass the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center, built with beds for 500 although it often houses 800 young people amid rampant vermin and loose ceiling tiles that can be used as missiles.

We cross a vibrant Mexican-American shopping street, each storefront brightly decorated, and then return to quiet working-class districts of brick homes. Next comes the Cook County Jail, set on 96 acres of city land, housing 9,800 inmates and employing more than 10,000 people, ringed by double coils of concertina wire. Family members wait in line by the maximum security wing.

And then vast industrial lots near the railway yards–historic sources of Chicago’s wealth and its solid jobs. The lots are still huge and busy, but now machines handle the containers and move the heaps of gravel. Hardly a human being is visible for blocks at a time, although I spot a fat black cat hunting in the tall weeds.