- Facebook183

- Threads

- Bluesky

- Total 183

Newly published: Levine, P. (2024). People are not Points in Space: Network Models of Beliefs and Discussions. Critical Review, 1–27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2024.2344994 (Or a free pre-print version)

Abstract:

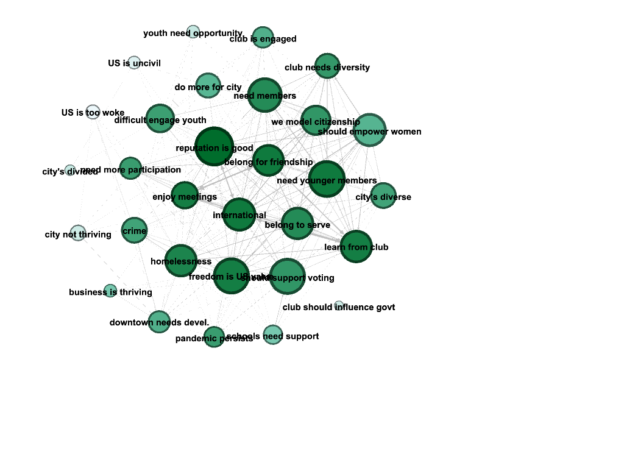

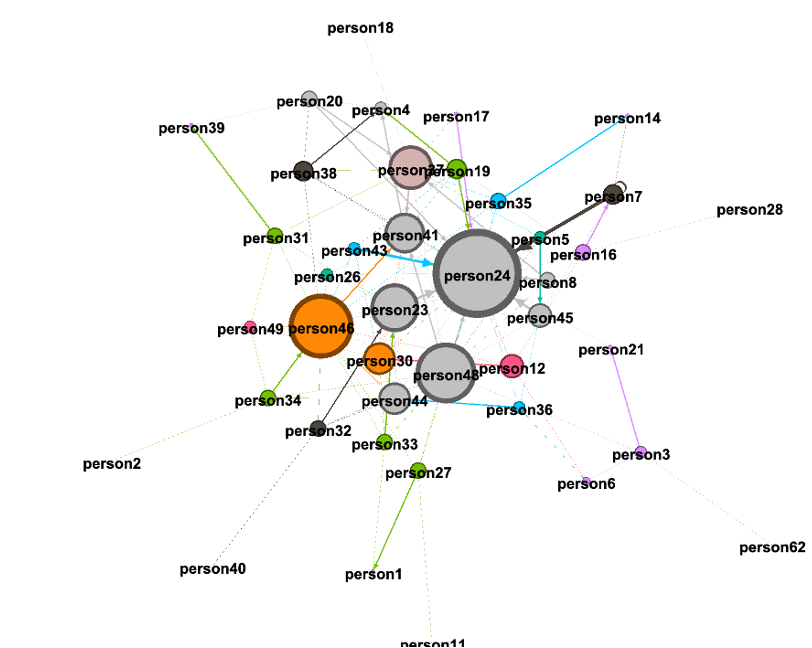

Metaphors of positions, spectrums, perspectives, viewpoints, and polarization reflect the same model, which treats beliefs—and the people who hold them—as points in space. This model is deeply rooted in quantitative research methods and influential traditions of Continental philosophy, and it is evident in some qualitative research. It can suggest that deliberation is difficult and rare because many people are located far apart ideologically, and their respective positions can be explained as dependent variables of factors like personality, partisanship, and demographics. An alternative model treats a given person’s beliefs as connected by reasons to form networks. People disclose the connections among their respective beliefs when they discuss issues. This model offers insights about specific cases, such as discussions conducted on two US college campuses, which are represented here as belief-networks. The model also supports a more optimistic view of the public’s capacity to deliberate.