- Facebook50

- LinkedIn1

- Threads1

- Bluesky1

- Total 53

I believe that left parties should draw their votes from lower on the socio-economic hierarchy, so that they can compete by offering more governmental support. Right parties should draw their votes from the upper end, so that they can compete by promising economic growth. This debate and competition is healthy.

In contrast, when left parties draw from the top of the social order, they tend to offer performative or symbolic policies, while the right promises low-SES voters some version of ethnonationalism. This debate is unhealthy because it blocks more effective and fair social policies, and it sets the right on a path whose terminus can be fascism.

Education is a marker of social class. We saw a social class inversion in the US 2024 election, with Harris getting 56% of college graduates and Trump getting 56% of non-college-educated adults.

Nowadays, we are used to assuming that Republicans have an advantage in the Electoral College because they are dominant in the states with the lowest percentages of college gradates, while Democrats win easily in the most educated states. But the opposite should be true.

I am fully aware that race is involved in the USA. Recently, less-educated white voters have formed the Republican base, whereas voters of color have preferred Democrats, regardless of their social class. However, in 2024, we saw a significant shift of low-education voters of color toward Trump.

Besides, race plays different roles in various countries, but many countries display a trend of lower-educated people preferring the right and moving in that direction .

The World Values Survey has periodically surveyed populations in 102 countries since 1989, for a total sample of almost half a million individuals in the dataset that I used for this post. The WVS asks most respondents to place themselves on a left-right spectrum, and the global mean is somewhat to the right of the middle. It also asks people their education level. For the entire sample, the correlation between these two variables is slightly negative and statistically significant (-.047**). In about two-thirds of sampled countries, the correlation is negative. This pattern is upside-down, suggesting the people with more education tilt mildly to the left around the world.

However, considering the heterogeneity of the countries and years in this sample (from Switzerland in 1989 to India in 2023), it is important to break things down.

The graph with this post shows the correlations for wealthy countries with democratic elections: the EU countries, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. A positive score indicates that people lower on the educational spectrum are more likely to vote left. The trend is slightly downward, meaning that the highest-educated have moved a bit left (and the lowest have moved right).

Among the countries that have recently demonstrated a class reversal (with the lower classes voting right) are Australia, Canada, Greece, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, the UK and the USA. Czechia and Slovakia are the main exceptions. In Japan and South Korea, less educated people have consistently favored the right to a small degree.

By contrast, for a sample of Latin American and Caribbean countries, the trend has generally been toward what I consider the desirable pattern, with lower-educated people increasingly voting left. The mean for all voters in this region is distinctly left of center.

In a cluster of countries that were part of the Warsaw Pact and are not now members of the EU, the trend is flat. Interestingly, in these countries, the mean voter is on the right.

Finally, the WVS surveys in some countries from the Global South–from Bangladesh to Zimbabwe-but these countries do not seem representative of the whole hemisphere. For what it’s worth, the trend for this sample is just slightly upward, and the results vary a great deal among countries.

I am still in the “deliverism” camp, believing that left parties have not delivered sufficient tangible benefits to less advantaged voters since the 1990s. (One explanation could be their dependence on affluent voters, who do not really want them to do much.) Achieving more tangible change could turn things right-side-up again.

However, it should give us pause that the Biden Administration actually spent trillions of dollars in ways that will benefit working-class Americans, yet Trump won and drew an increasing proportion of lower-educated voters of color. The “deliverist” thesis now depends on the premise that Biden-Harris had too little time and suffered from post-COVID inflation.

Meanwhile, if your premise is that US working-class voters moved right due to (increasing?) racism and sexism, you need an explanation of similar trends in many countries, including some without substantial ethnic minorities.

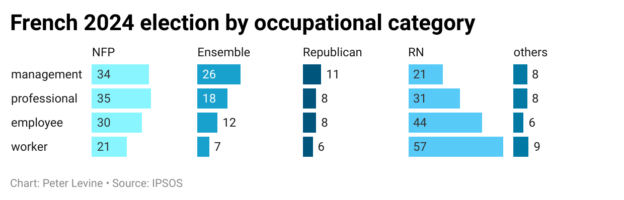

See also: class inversion in France; social class inversion in the 2022 US elections; class inversion as an alternative to the polarization thesis; the social class inversion as a threat to democracy; social class and the youth vote in 2024; social class and political values in the 2024 election; why “liberal” can sound like “upper-class”; UK election results by social class; social class in the French election (2022); and encouraging working class candidates