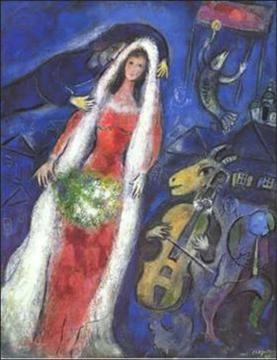

Marc Chagall was not a major artist, in my opinion. He was a decorative illustrator who developed a distinctive and memorable overall style without producing any particularly memorable works. As Richard Dorment wrote recently in the New York Review, we value Chagall mainly for what he remembered and depicted. He painted nostalgic fantasies of the Eastern European Jewish world that was ruthlessly destroyed–along with almost all of its people–during his lifetime. In my view, Chagall’s art, his biography, and the cataclysm around him combine to make something worthy of space on museum walls.

The irony is that Chagall–a poor kid from a provincial backwater–had the privilege of joining two sophisticated modernist movements: Cubism in Paris and then Suprematism in Moscow. (The Suprematists are most famous for Kasimir Malevich’s “Black Quadrilateral on White,” the first completely abstract painting.)

The Cubists and the Suprematists were committed to the great modernist project of transcending arbitrariness. When a traditional painter used a Renaissance style to depict the Virgin Mary in order to illustrate Catholic ideas, the modernist saw layers of arbitrariness. They asked: Why Mary? Why Catholicism? Why a vanishing point in the middle of the rectangular canvass? None of these questions had answers that would really count unless one belonged to the culture of the artist, sharing his biases and beliefs. One could appreciate such art from a cultural distance–but only because of its emotion and its form. So why not strip art down to those two essentials? Malevich wrote: “Suprematism is the rediscovery of pure art that, in the course of time, had become obscured by the accumulation of ‘things.’ … The new art of Suprematism … has produced new forms and form relationships by giving external expression to pictorial feeling.”

Chagall didn’t paint that way, and it is possible that he did not even understand these ideas. Maybe he would fail an art history exam about the work of the masters whom he knew personally. Richard Dorment says so: “And just as he had assimilated Cubist form without, I think, necessarily understanding it, so now he appropriated Suprematist style without having the slightest idea that for Malevich abstraction was a means toward the elimination of the self in order to achieve a higher level of spiritual experience. Chagall wasn’t an explorer and he wasn’t an intellectual.”

Right, but he was a witness with a memory, and we can appreciate his painted memoirs for what they depict. Meanwhile, Malevich is not interesting or important because of his monochrome rectangles. He is important because he created them, along with radical manifestos, on the eve of the Soviet Revolution. In other words, his pictures belong to an interesting story that also involves his biography and the historical context. If all art–including High Modernism–is contextual, contingent, embedded, narrative, immanent, and local–then it’s hardly an accusation to say that Chagall illustrated his own past. Malevich did the same thing, unwittingly. He illustrated the moment of revolutionary ferment around 1914. The question is the quality of Chagall’s illustrations (and about that, I must say I have mixed feelings).