- Facebook660

- Total 660

The Democracy Fund’s Voter Study Group has released an important new paper by Emily Ekins entitled, “Religious Trump Voters: How Faith Moderates Attitudes about Immigration, Race, and Identity.”

Ekins notes that Trump performed best in the 2016 GOP primaries among Republican voters who never attend church (getting 69% of their vote). Examining Trump voters during 2018, she finds correlations between regularity of church attendance and positive attitudes toward racial and religious minorities, acceptance of diversity, approval of immigration (and opposition to the border wall), and concern about poverty.

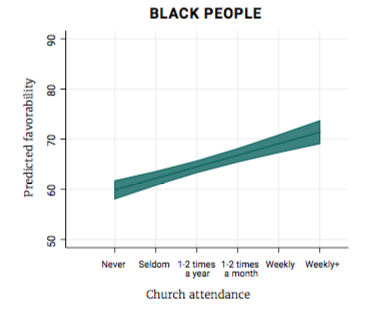

Here I illustrate that pattern with attitudes toward Black people as the dependent variable. The trend line controls for race, gender, income, education, and age. All the data come from Trump voters. Because the correlation between church attendance and racial attitudes among Trump voters holds with these controls, Ekins suggests that it is causal.

This might not be a case of cause-and-effect. A third factor might underlie both tolerance and church attendance. However, I posited a similar causal hypothesis early in 2017, after I’d met with a conservative Southern pastor who despised Trump’s leadership style and attitudes. This pastor blamed Trump’s support on coach-potato “Christians,” those for whom Christianity is an identity rather than an actual faith, those who get their ideas from Fox News or Breitbart, not from fellow congregants.

Some colleagues and I tried to test this hypothesis using survey data and failed to find it, which is a null result worth noting. Still, I’d like to think that Ekins is right—perhaps more so in 2018 than in 2016.

Why would this pattern hold?

First, Ekins shows that church-attending Trump supporters volunteer and trust other people much more than Trump supporters who rarely or never attend Church. It may be that people who help others and feel they can rely on others are less likely to despise and fear strangers. In turn, church-attendance may promote volunteering and trust, or it may manifest a broader form of social capital that explains both tolerance and church-attendance.

Robert Putnam introduced a distinction between “bridging” and “bonding” social capital. The bridging kind connects people who are diverse in some respects; the bonding kind may increase solidarity in opposition to outsiders. One could imagine that churches enhance bonding social capital. America is said to be most segregated on Sunday mornings, and churches distinguish insiders from outsiders. But volunteering and trusting generic others are measures of bridging, not bonding, social capital. Insofar as churches encourage volunteering, they are trying to create bridging social capital.

Another mechanism could be leadership. Real churches have leaders, both clergy and laypeople. Church leaders are expected to be responsive and responsible and to hold the group together. In contrast, Trump just says whatever comes into his mind, usually makes no effort to deliver what he promises, and is happy to divide. I have hypothesized that people who are familiar with real leadership in local voluntary associations would despise Trump’s style. Although we were unable to show that pattern using survey data, Ekins’ new results may suggest that it holds.

A third mechanism could be the content of the faith. I happen not to be religious, and I could criticize the specific content of many sermons and texts on ethical grounds. I am aware that there are mega-churches that show huge audiences jingoistic videos of American military might; there are clerics who praise Trump or cite Romans 13 to defend the administration’s policies. In my opinion, these examples are idolatrous as well as unjust, but my argument does not depend on romanticizing the content of religious expression.

I would argue, instead, that real faith is demanding. You can find passages and examples that reinforce bigotry, but you will also encounter texts that challenge you. Faith may be consistent with almost any policy position—as we can see from the enormous range of political opinions among clergy—yet participation in a deep and complex religious community is inconsistent with all simplistic attitudes about other people. Cable news and propagandistic websites reinforce what their audiences want to hear, but scripture is strange and demanding. Since religious texts are very hard to figure out by oneself, they require discussion and debate. In turn, the people in any given discussion usually turn out to have idiosyncratic and incompatible interpretations. This is why Martin Luther, despite his break with The Church, believed that we all need a church to keep us honest. Even if the content of preaching and liturgy doesn’t turn us into people who understand and care for others, the decision to attend a service may reflect a desire to become such a person.

In short, religion as a pure identity: bad. Religion as a community of people who struggle to address issues of moral and existential importance: good. Voters who actually attend church are more likely to experience the good form of religion, compared to those who identify as Christians without showing up on Sunday.

See also: the prospects for an evangelical turn against Trump; the Hollowing Out of US Democracy; why Trump fans aren’t holding him accountable (yet); and why Trump fans aren’t holding him accountable (yet)