The great social theorist Jürgen Habermas has drawn attention–for more than half a century–to the problem that he calls the “colonization of the Lifeworld by System.” Here is my explanation, based mainly on a rare concrete example from his Theory of Communicative Action, vol. 2.

The Lifeworld, for Habermas, is the background of ordinary life: mainly private, somewhat naive and biased, but also authentic and essential to our satisfaction as human beings. It is a “reservoir of taken-for-granteds, of unshaken convictions that participants in communication draw upon in cooperative processes of interpretation.” In the Lifeworld, we mostly communicate with people we know and who share our daily experience, so our communications tend to be opaque to outsiders and certainly not persuasive to people unlike us. But Habermas argues that we are incapable of thinking about everything at once. In order to reason and communicate, we must take most points as givens. Only then can “single elements, specific taken-for-granteds” be brought up for conversation and critical analysis.

Meanwhile, the “System” is composed of formal organizations, such as governments, corporations, parties, unions, and courts. People in a System have official roles and must pursue pre-defined goals (albeit sometimes with ethical constraints). For example, defense lawyers are required to defend their clients, corporate CEOs are supposed to maximize profit, and comptrollers are supposed to reduce waste in their own organizations. In the current period, there are fundamentally two Systems: markets (in which instrumental action leads to profit) and governments (in which instrumental action demonstrates power). Although the people who work in markets and governments are complex individuals with other commitments, their official work responsibilities are to maximize money or to administer power.

To illustrate the Lifeworld, Habermas invites us to envision an “older construction worker who sends a younger and newly arrived co-worker to fetch some beer, telling him to hurry up and be back in a few minutes.” The senior worker assumes that a whole set of beliefs and values are shared on the team: German construction workers enjoy and expect to drink beer at breaks during the workday, beer is for sale in the vicinity, the younger and/or most recently hired person is the one who does unpaid chores for the group, and so on. Each of these assumptions could be brought into doubt and subjected to debate. For instance, as Habermas suggests, the younger worker might say, “But I don’t have a car,” or “I’m not thirsty.” Other “elements of the situation” might generally pass unnoticed yet become relevant as circumstances change. If the younger worker is an immigrant without health coverage and he falls off the ladder as he goes to buy the beer, several relevant laws and controversies may suddenly occur to the workers, moving from their background knowledge to topics of explicit discussion. But at any given moment, simply by virtue of being human, the workers must assume most features of the situation as a shared and implicit background, a “vast and incalculable web of presuppositions.” This is their Lifeworld.

In order for the workers (or any other group of people) to be free and self-governing, they must be able to render any aspect of the Lifeworld problematic. It is a definitive feature of modernity that no assumptions are considered immune to critique; and it is a condition of democracy that no critique is blocked by law or other force. When the younger construction worker notes that no beer is available within walking distance and he doesn’t have a car, he is giving a reason for someone else to go. This turns his work group into a small Public Sphere. To the extent it is democratic and deliberative, his reasons will require responses.

Imagine (to go beyond Habermas’ presentation of this example) that the radio is playing as these men work. A news program includes an interview with a feminist activist who criticizes the construction industry for hiring very few women, followed by an immigrant leader who notes that alcohol is forbidden to Muslims (thus the assumption that everyone wants to drink beer is exclusionary), followed by a health expert who attributes disease to excessive daytime beer consumption. These people are making arguments that compel critical attention to specific aspects of the workers’ Lifeworld. They represent the larger Public Sphere of the Federal Republic or the European Union. It doesn’t matter whether the interviewees have self-interested motivations, such as selling copies of their books, or whether the radio station is a for-profit company trying to attract listeners. The format of any reasonably well-run news program will compel the speakers to give reasons that can be checked and assessed by reporters and listeners. This is a case of a democratic Public Sphere challenging citizens to reflect about aspects of their Lifeworld.

But although every particular point should be subject to discussion, the whole Lifeworld must be protected. One reason is that we need the Lifeworld to think at all, for we are capable of testing a specific assumption only while holding our other assumptions for granted. A second reason is that our Lifeworld is ours, a condition of living authentically. Any political program that tries to strip a group of people of their accumulated assumptions all at once would be totalitarian. A radio program that brings separate issues to the workers’ attention expands their thinking; but if a revolutionary government seizes all the radio stations and begins broadcasting propaganda against contemporary German working-class culture as a whole, that is a threat to their Lifeworld.

Meanwhile, the Lifeworld is vulnerable to manipulation by interested parties who act instrumentally. For example, suppose that on the radio, the workers hear men with similar accents to their own praising a particular brand of beer. Maybe women are also heard, enjoying these men’s company and appreciating their good taste. It sounds as if friends have entered the real Lifeworld of the construction site, but these supposed friends are really actors who are are paid to sell beer. Of course, the workers will understand the purpose of an advertisement, yet by skillfully imitating their authentic Lifeworld, the ad can affect their behavior. No reasons need be given; no rebuttal is invited. In this case, Habermas would say that the Lifeworld of the workers has been colonized by the System of markets. The System of government might similarly colonize their Lifeworld if a candidate for public office started talking on the radio as if he were their friend who shared their values and experiences.

In discussions of Systems colonizing Lifeworlds, common examples include commercial advertisements that masquerade as authentic communications. These are cases of “commodification”: firms mining the Lifeworld for economic advantage. Habermas also emphasizes the tendency of welfare state bureaucracies to “juridify” or “judicialize” the Lifeworld. For instance, when well-intentioned states seek to protect pupils and parents against unfairness in testing and discipline, fairness “is gained at the cost of a judicialization and bureaucratization that penetrates deep into the teaching and learning process,” depersonalizing the school, inhibiting innovation, and undermining relationships.

A neo-Marxist line of criticism faults Habermas for equating juridification with commodification and the state with the market. This critique hold that the underlying process is capitalist exploitation, and the welfare-state is only a threat to the Lifeworld because it is a tool of capital. Habermas disagrees. For him the underlying process is growing specialization, a feature of modernity. He insists that in socialist societies, the state colonizes the Lifeworld in a parallel way to the market’s colonization in capitalist societies; and in welfare states, both threats operate at once.

[It turns out that I have posted 58 times before on Habermas, collected here. My broadest posts are probably Habermas and critical theory (a primer); saving Habermas from the deliberative democrats; and Ostrom, Habermas, and Gandhi are all we need.]

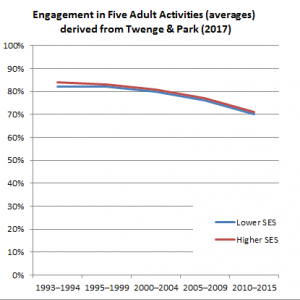

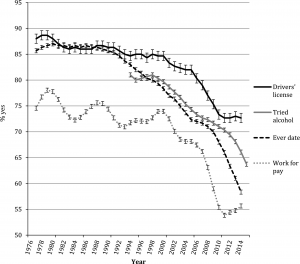

A new paper by Jean Twenge and Heejung Park (2017) is getting a lot of coverage. The main finding is a delay in the onset of certain activities traditionally defined as “adult.” This graph shows the trends in having a driver’s license, drinking alcohol (ever), dating, and working for pay–all down steeply for teenagers.

A new paper by Jean Twenge and Heejung Park (2017) is getting a lot of coverage. The main finding is a delay in the onset of certain activities traditionally defined as “adult.” This graph shows the trends in having a driver’s license, drinking alcohol (ever), dating, and working for pay–all down steeply for teenagers.