I am in Washington, DC but remembering our winter vacation in Les Saintes, near Guadeloupe, because I am reading Derek Walcott’s astoundingly good epic, Omeros.

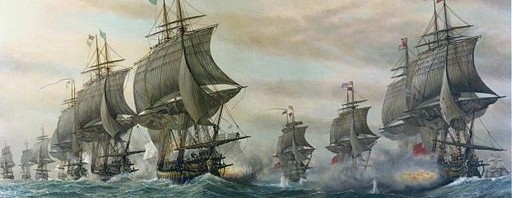

In the channel with three islets christened “Les Saintes”

in a mild sunrise the ninth ship of the French line

flashed fire at The Marlborough, but swift pennants

from Rodney’s flagship resignalled his set design

to break from the classic pattern … (XV)

Walcott is referring here to a major naval battle in 1782. When we saw the dioramas of the battle in the local history museum, I wondered why the “classic pattern” was for enemy fleets to form neat parallel lines and blast away at each other.

Was this some kind of courtly custom of the Baroque era? (Walcott writes, “the young midshipman … thought there was no war /as courtly as a sea-battle.”) I think game theory offers a better explanation. The opposing players chose the best available strategies, each on the assumption that his opponent would make the best choice for him–which is what game theorists call a Nash Equilibrium.

Recall that sailing vessels cannot maneuver with perfect control because they are driven by the wind. Most of their lethal fire is directed from their sides. If they independently choose their own courses during a battle, they can easily get in each others’ way. In principle, each could be given complex directions from some central point, but inter-ship communication was badly limited before radio. It therefore made the most sense to set one simple rule that would guarantee coordination. The inflexible rule of the Royal Navy was to form a line of evenly spaced vessels.

Lord Howe’s Explanatory Instructions (1799) explained, “The chief purposes for which a fleet is formed in line of battle are: that the ships may be able to assist and support each other in action; that they may not be exposed to the fire of the enemy’s ships greater in number than themselves; and that every ship may be able to fire on the enemy without risk of firing into the ships of her own fleet.”

If one fleet had a good reason to form a line of evenly spaced ships, so did its opponent. Both wanted to sail in front of the other’s line, or “cross the T,” so as to be able to rake the enemy’s ships without receiving fire in return. But if two fleets are both trying to cross in front of each other, what you get is a pair of parallel lines.

The result of such a battle was pretty predictable, a function of the number of guns on each side. That meant that a clearly smaller fleet had a strong incentive to avoid battle or, if forced into it, to break the line and take a chance at prevailing in a chaotic melee. A melee could also develop by accident as a result of weather conditions, geographical obstacles, or sheer chaos. At the Battle of the Saintes (1782), the lines got mixed up. Walcott says this was Admiral Rodney’s plan, his “set design.” Wikipedia says the reason was a gusty wind that broke up the lines. Whether by chance or design, the Royal Navy ended up killing 8,000 French to their own losses of just 243 men.

Trafalgar (1805) was another famous counterexample. Nelson deliberately swooped in to break the enemy line, despite the grave risk of being raked by their broadsides, because he had a much greater incentive than the Franco-Spanish fleet to achieve a decisive result that day and was willing to take his chances. Nelson played the chicken game and didn’t swerve, for which he paid with his life but gets to stand on top of a huge column in central London to this day.

In 1913, when he was First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill faced the accusation that he had impugned the traditions of the Royal Navy. He replied: “And what are they? Rum, sodomy and the lash.” Maybe he should have said, ” … and the Nash.”

See also the gift economy of Beowulf and some thoughts about game theory.