(Indianapolis) I’m attending a meeting on teacher education. During a morning session on the teaching of American history, there was some criticism of a certain national historical narrative that’s often retold by children when they are asked what they’ve learned in school. According to this story, from time to time, Americans have realized that there are problems, such as slavery or segregation; and then the government has solved each problem by law.

Even though this is a celebratory and patriotic narrative, it’s not a conservative one. It emphasizes progress by and through government, contrary to a truly conservative national history, which would begin with a self-reliant, faithful people and end with a decadent welfare state. For similar reasons, conservatives should dislike the patriotic iconography of official Washington, with its monuments to Jefferson and Washington as the founders of the government that now occupies vast marble office buildings (including the 3.1 million-square-foot structure named for Ronald Reagan). Certain kinds of populist or participatory leftists may be equally hostile to the progressive/statist story, because it ignores citizens and their agency.

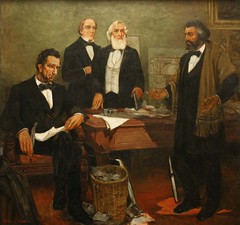

With such thoughts in my mind, I walked over to the Indiana State Museum and saw an exhibition of paintings by William Edouard Scott (1884-1964), an African American artist born in Indianapolis and educated in Chicago and Paris. His works tell a strongly progressive narrative of American history, although not one centered on the government. An easel painting (“Freedom,” 1960) shows, from bottom to top, Crispus Attucks being shot by the British in 1775, John Brown (1850), “Abe Lincoln and Fred Douglas” (1863), Thurgood Marshall raising his hand to testify (1954), and an eagle marked “NAACP” downing a bird marked “KKK.”

In 1915 alone, Scott painted 20 murals in public high schools in Chicago and Indianapolis. The same year, he painted murals for the office buildings of the Chicago Defender, a major African American newspaper. The Defender editorialized, “When our new buildings are decorated by the works of our own artists we are contributing something substantial to American progress, especially if we obtain the services of well trained men or women.”

Note the evocations of racial identity and solidarity, contributions to the American commons, progress, patriotism, excellence, expertise, and equality of women and men. This was a common kind of discourse in the mid-1900s, and one that the state sometimes funded. For instance, Scott won a Federal Arts Project competition in the war year of 1942 to decorate the Recorder of Deeds building in Washington, DC. He produced a mural — shown above — of Frederick Douglass appealing to President Lincoln to enlist Black troops in the Union Army. (Douglass himself became the Recorder of Deeds in 1881.) Credit: dbking; some rights reserved.