- Facebook69

- Twitter1

- Total 70

Perhaps each species has a different “umwelt,” a unique enveloping environment that is experienced and influenced by the organism’s sensory organs and nervous system. In that case, reality is not one connected thing, but rather everything that you can I could possibly experience and describe, plus the many other universes that are “enacted” (Varela, Thompson & Rosch 1991) by other species–those known and unknown to us, existent and yet to be.

Reflecting on such radical unknowability may have spiritual implications, which have been explored in different ways by Dogen (1200-1253 CE), Ludwig Wittgenstein, and others. (See “thinking both sides of the limits of human cognition.”)

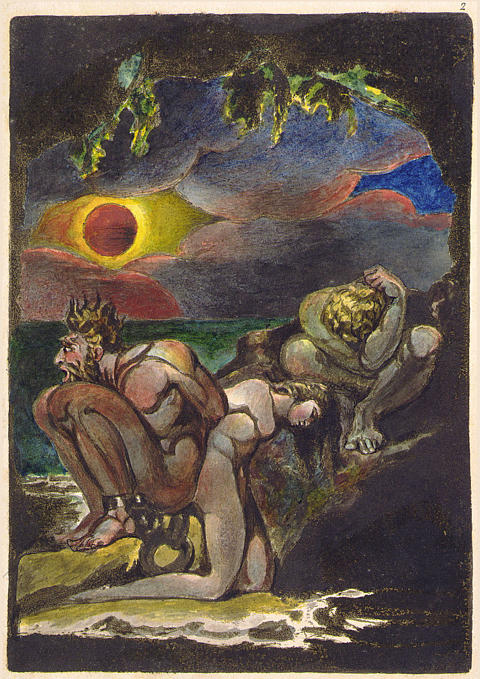

William Blake presents a relevant discussion in his Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793). Oothoon–a female figure, described as “the soft soul of America”–invokes the radical diversity of animal experiences, “as different as their forms and as their joys.” She implies that the consciousness of the chicken, pigeon and bee are fundamentally different. She uses such examples to pose a question about our own consciousness:

Ask the blind worm the secrets of the grave, and why her spires Love to curl round the bones of death; and ask the rav’nous snake Where she gets poison; and the wing’d eagle why he loves the sun And then tell me the thoughts of man, that have been hid of old. Blake, Selected Poems, Penguin Classics (p. 63).

I am not sure whether she is inviting us to imagine the experience of eagles and worms, or whether she assumes this would be impossible. Later, she exclaims, “How can one joy absorb another? are not different joys / Holy, eternal, infinite! and each joy is a Love” (p. 65).

This is a plea for appreciating fundamental diversity. She uses it to ask the person she loves, Theotormon, to accept her for who she is.

Blake had been exploring arguments for empathy. In his poem The French Revolution (1791), the pro-republican Duke of Orleans says to his reactionary peers:

But go, merciless man! enter into the infinite labyrinth of another's brain Ere thou measure the circle that he shall run. Go, thou cold recluse, into the fires Of another's high flaming rich bosom, and return unconsum'd, and write laws. If thou canst not do this, doubt thy theories, learn to consider all men as thy equals, Thy brethren, and not as thy foot or thy hand, unless thou first fearest to hurt them.

Blake may not endorse Orleans’ belief that one can actually enter others’ brains. I am not sure whether he thinks such radical empathy is virtuous or impossible. Either premise could be the basis for appreciating everyone’s uniqueness.

Bromion is a (very bad) male character in the Daughters of Albion. He replies to Oothoon by acknowledging that there are many

... trees[,] beasts and birds unknown: Unknown, not unpercievd, spread in the infinite microscope, In places yet unvisited by the voyager and in worlds Over another kind of seas, and in atmospheres unknown (p. 64).

Bromion then poses a series of questions about whether there are different wars, sorrows, and joys for these creatures. I think his answer is No:

And is there not one law for both the lion and the ox? And is there not eternal fire, and eternal chains? To bind the phantoms of existence from eternal life? (p. 65)

Here Bromion explicitly contradicts an aphorism from Blake’s “Proverbs of Hell” (1790)– “One Law for the Lion & Ox is Oppression” (p. 58)–which makes me suspect that Blake is against Bromion’s view.

The third speaker in The Daughters of Albion is Theotormon. He asks Oothoon to share what she knows of the world, “so that [he] might traverse times & spaces far remote.” But he is not sure what this will do for him:

Where goest thou O thought! to what remote land is thy flight? If thou returnest to the present moment of affliction Wilt thou bring comforts on thy wings, and dews and honey and balm; Or poison From the desart wilds, from the eyes of the envier?’ (p. 64).

Theotormon is worried that empathy might cause envy or other harms. But Oothoon is sure that any experience of a consciousness other than one’s own is beneficial. She concludes the poem: “Arise and drink your bliss, for every thing that lives is holy!’ (p. 68). Theotormon sits silently while the other daughters of Albion “echo back her sighs.”

See also: civility, humility, tolerance, empathy, or what?; compassion, not sympathy; Gillray and Blake; and “you should be the pupil of everyone all the time”