- Facebook33

- Twitter2

- Total 35

Here is what I will call a “top-down” theory of public opinion: Everyone should assess the most important issues of the day. An example might be the federal budget. Individuals are entitled to their personal beliefs or preferences about taxation, spending, and deficits; nevertheless, these three topics have an objective logical structure. If you want lower taxes and no deficits, you must favor spending cuts. If you want more spending, you must support either tax increases or bigger deficits. It is a civic obligation to think through your own complete view of these issues.

Analyzing a nationally representative survey of such matters should reveal that: a) most citizens hold opinions about them, and b) everyone recognizes the same underlying logic, even as they disagree about priorities. Citizens should vote according to their priorities, and the majority should prevail.

If, however, a) and b) are false, then democracy is flawed. Perhaps people should learn more and pay more attention, or the political system should offer greater clarity, or perhaps democracy is simply a false ideal.

Philip Converse’s “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics” (1964) has been enormously influential (cited more that 11,000 times). He does not employ exactly the framework with which I began this post, but his analysis suggests that democracy is a flawed ideal.

Analyzing surveys of political specialists, such as congressional candidates, Converse finds that these respondents meet both tests mentioned above. Professional politicians and other experts hold opinions on the great issues of the day that fit together in similar ways, even as they debate the contested questions. However, according to Converse, surveys of representative Americans reveal scant opinions and no consistent structure among opinions. Ordinary people are not, therefore, in a position to weigh in on the debates of the day.

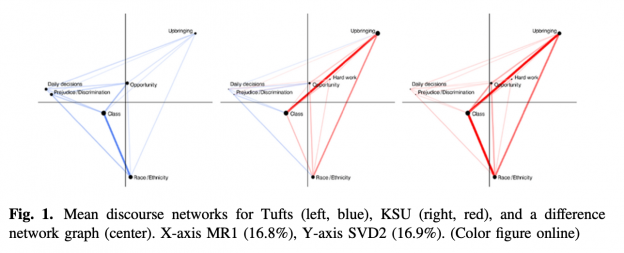

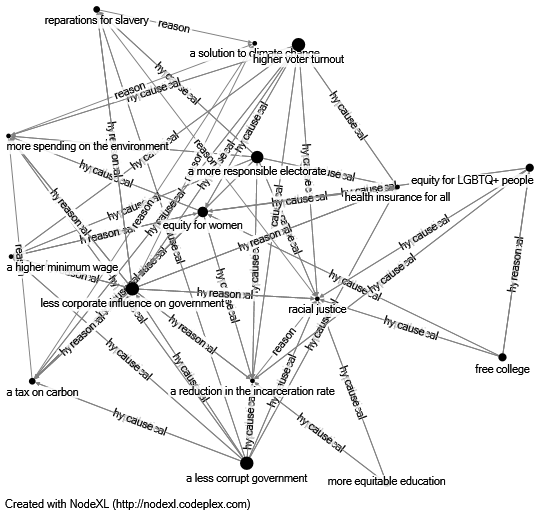

Converse doesn’t use network analysis, but I can convert his core findings into network maps. (For those interested, I turned every tau-gamma coefficient above .05 in Converse’s Table 7 into an edge in these graphs.)

Congressional candidates share the following model of the political debate ca. 1962.

Whether candidates are Democrats or Republicans is strongly related to their views of federal interventions on education, housing, and employment, and those issues are linked together. Military aid to foreign countries is not connected–it stands alone as a topic. (“FEPC” means the proposed Fair Employment Practices Commission.)

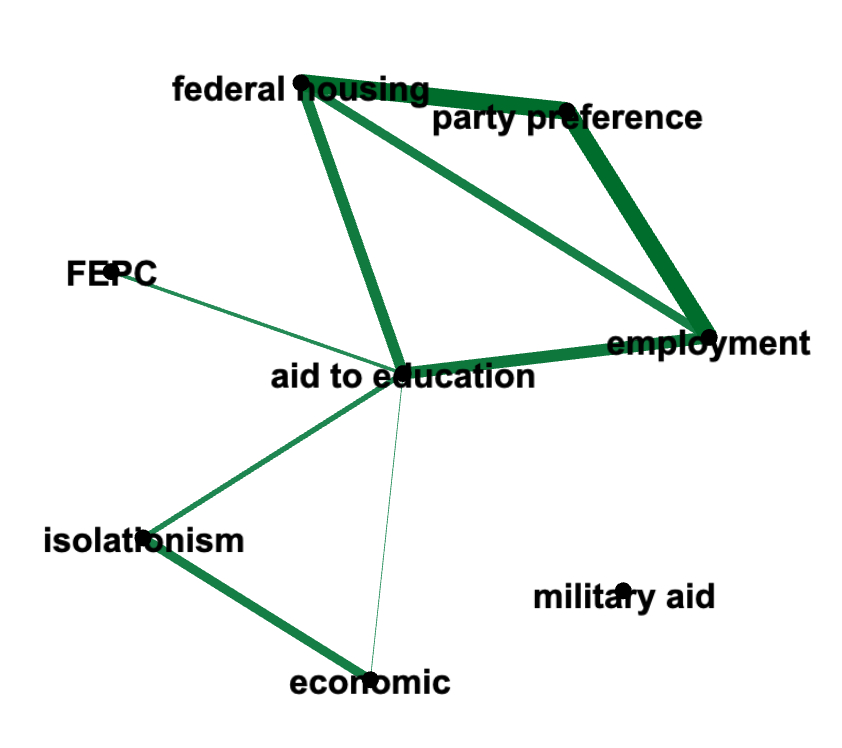

Meanwhile, this is the result of using the same method with Converse’s data from representative adults at the same time:

There are no links at at all among the ideas (meaning no coefficients > .5). Converse suggests that people are not in a position to play the role expected in a “civics class” theory of democracy, assessing and voting on the issues of the day.

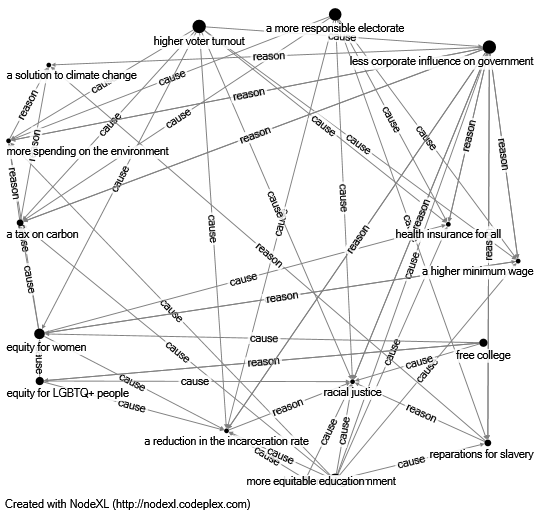

Now here is a rival, “bottom up” theory: The social world is enormously complex. Responsible people may hold opinions on myriad issues, and no one can have a view about everything. Even if we focus on a single domain, such as the federal budget, it is highly complex. Federal spending includes funds for many different purposes. Each federal program has a financial cost, but it also has moral significance, behavioral impact, symbolic meaning, likelihood of success, etc. If people are diverse and free, they will naturally form many different structures of opinions about the range of topics that they have considered so far.

Imagine a sample of people, each of whom holds a thoughtful and carefully considered view of public issues and connects each opinion to other opinions in rigorous ways. However, each person holds a unique structure. Then, if researchers contact each person and ask a short list of survey questions (out of the innumerable questions that they could ask), and the aggregate survey data is analyzed using the methods pioneered by Converse, it will reveal no significant links at all. The heterogeneity of individuals’ beliefs will yield very low coefficients at the group level. Their graph will look just like the second graph above–not because they are tuned out of politics or undisciplined in their thinking, but because they differ.

Converse (p. 44) explicitly acknowledges this possibility. He notes that if people’s opinions become “increasingly idiosyncratic” as they move away from the elite, we will find “little aggregative patterning of belief combinations” in their data, because they will not know “what goes with what” (presumably, according to the elites) and will “therefore put belief elements together in a great variety of ways.”

However, Converse counters with a different kind of evidence. According to his analysis of longitudinal data from the American National Election Studies from 1958-60, most people’s opinions on most issues change as if by sheer chance as time passed. This implies that they do not hold “well knit but highly idiosyncratic belief systems” (p. 47). Instead, they have no “meaningful beliefs” at all (p. 51). The exceptions are various small and specialized “issue publics” who hold stable opinions about specific concerns, including many Blacks and some White Southerners on questions of race.

On this point, I would only note that an enormous number of longitudinal studies have been conducted since 1962, and some find stability over time (e.g., Kustov, Laaker & Reller 2021), unexplained–and perhaps random–change (Jaeger, M. M. 2006), or a mix of the two, depending on this issue (Kiley & Vaisey 2020). For instance, according to the last of those studies, the proportion of individuals who change their opinions about abortion is extraordinarily low. Converse’s blanket claim that most people’s opinions on most issues change randomly seems overstated.

I do not assume that all of my fellow Americans (or anyone else) holds complex and rigorous mental models of politics. Some people hardly hold any opinions, or cannot connect their opinions together, or do so in illogical ways. My point is that we cannot tell from aggregate data what proportion of people hold thoughtful views unless we assume that all worthy views must manifest the same structure. Converse uses scare quotes around the word “proper” when he mentions “the sophisticated observer’s assumption of what beliefs go with other beliefs,” but if we seriously doubt that elites understand the “proper” arrangement, then we should expect regular people to exhibit great diversity.

In that case, we should seek to understand the heterogeneous structures of ordinary people’s views. This kind of research has three important purposes:

- It may counter the very low assessment of public capacity that is fashionable now in political science, deriving from Converse. That skepticism may prove self-reinforcing, since experts who doubt the public’s ability to reason will not be motivated to defend or improve democracy.

- It may yield specific findings about structures of thought shared by sub-groups. Those insights will be invisible as long as we only we ask whether the public shares the structures assumed by political elites.

- It offers a perspective on political institutions. Even if many people hold worthy but heterogeneous structures of ideas, we probably still need mass elections to address prominent topics, such as whether to raise or cut taxes. I support that kind of democracy. But it will always be frustrating, because the structure presented by elites will fail to match the reasonable structures in many people’s minds. Fortunately, we can complement mass majoritarian democracy with other forms of participation. Civil society provides an enormous range of specialized groups, and individuals can choose to join the groups that match their personal ideologies, exit ones that don’t, advocate for adjustments within the groups they belong to, and compete for new members. Meanwhile, relatively small and relatively discursive bodies, such as local town meetings or Participatory Budgeting sessions, offer individuals opportunities to share their idiosyncratic views in public. We might understand those venues as opportunities for deliberation that can yield wiser judgments. Or we might understand such venues as places where people can display their uniqueness, as Hannah Arendt advocated. Thus a “bottom up” theory supports decentralization, pluralism, or polycentricity.

See also: Moral and Political Discussion and Epistemic Networks; modeling a political discussion; individuals in cultures: the concept of an idiodictuon; ideologies and complex systems; don’t let the behavioral revolution make you fatalistic, polycentricity: the case for a (very) mixed economy, etc. I also acknowledge Jon Green, Nic Fishman, Sarah Shugars, and others who are working in this general domain today.