This post is cross-posted from the Democracy Fund blog. It’s one in a series of posts about our evaluations of initiatives funded by the Democracy Fund.

During the 2012 campaign season, the Democracy Fund’s grantees experimented with a wide range of strategies to educate and engage the public. Some produced videos and other educational content to directly inform the views of voters. Others worked with journalists to improve the information that the public receives through local and national media. In all cases, CIRCLE’s evaluations found that the public’s polarization made it significantly more difficult for these efforts to achieve their goals; polarized individuals often resisted the messages and opportunities offered to them.

Americans perceive the nation as deeply divided along political lines. In February 2013, according to the Bipartisan Policy Center, 76 percent of registered voters said that American politics had become more divisive lately and 74 percent believed that this trend was harmful. Academics disagree somewhat about the degree of polarization and whether it has become worse over time, but few doubt that political polarization can exacerbate fear and distrust, prevent people from understanding alternative perspectives and considering challenges to their own views, and reduce the chances of finding common ground.

The challenges of engaging polarized citizens emerged clearly in CIRCLE’s evaluations. For example, Flackcheck.org produced parody videos that taught viewers to reject deceptive campaign advertisements. In testing whether these videos were effective, we showed representative samples of Americans real campaign advertisements that we considered misleading. One example, “Obamaville,” produced by Rick Santorum’s campaign, displayed President Obama’s face alternating with that of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad on a television screen in a post-apocalyptic setting:

More than 80% of Democrats but fewer than 20% of Republicans considered this video “invalid and very unfair.” Among the Republican viewers, some made comments like this:

-

“It does make him look like a threat…He is a threat to the United States and the well being of the people and welfare of our country…”

-

“Tells the truth about Obama”

-

“TO SHOW VERY CLEARLY WHAT OBAMA IS DOING AND TAKING THIS BEAUTIFUL COUNTRY! BELIEVE IN OBAMAVILLE”

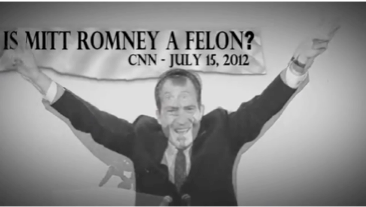

We showed a different sample of respondents a MoveOn advertisement entitled “Tricky Mitt,” in which Mitt Romney’s image faded into Richard Nixon’s:

More than 70% of Republicans and less than 10% of Democrats considered that video “invalid and very unfair.” Some Democrats made critical comments about “Tricky Mitt” (e.g., “Accusatory, urges the viewer to associate guilt with Romney, not reflective of what I expect from politicians”), but many were positive about the video, saying things like this:

- “Excellent”

- “Entertaining and points out the crookedness of Romney”

- “Giving us information that we didn’t know about. All true”

- “I think it exposed the truth about Romney of what kind of person he really is.”

Essentially, people approved of ads that supported their own partisan position and criticized or invalidated ads that threatened their preexisting beliefs, although both ads we tested were deceptive.

We also evaluated Bloggingheads.TV videos, which showed pundits of opposite political persuasion taking part in civil discussions about controversial issues. We asked people who watched various videos a scale of questions that measured their openness to the other side. An example of a question in this scale was “I have revised my thinking on the issue.” Regardless of which video they watched, the strong partisans were always less open to deliberation.

Strongly polarized statements also emerged in many of the open-ended questions that CIRCLE asked of Democracy Fund grantees. For example, we asked a representative sample whether they ever shared political videos. Out of 195 respondents who chose to explain why they did so, 24% mentioned anti-Obama goals, often adding very strongly worded comments against the president. (“Obama confessing to being a Muslim”; “A black heavy set lady going on about Obama care, and that we should go ahead and work to pay for her insurance”; “Michelle Obama whispering to B.O., ‘all this over a flag!’”; “I come from a military family and I am extremely offended by the both of them. I have never seen a more un-American couple in the White House!”). Another 17% percent mentioned anti-Romney videos, often the Mother Jones video about the “47%.”

Some of the Democracy Fund grantees did not directly influence average citizens, but rather worked to support professionals in newspapers or broadcast stations. In general, these journalists, editors, and station managers seemed less prone to partisanship than average citizens. However, some reporters expressed skepticism about the neutrality of Flackcheck.org and wondered whether it had a partisan agenda. “I am suspicious of so-called non-partisan fact checkers,” one said. A broadcast station-manager, asked how he or she would react to being told that a given ad was misleading, said, “It would be difficult to determine the true nature of the intent [behind the criticism] or that the third party was indeed unbiased.”

These responses suggest that an atmosphere of polarization and distrust may create challenges even for organizations that work with nonpartisan professionals. Going forward, the Democracy Fund and its grantees may consider a range of possible strategies, such as:

-

Focusing at least some attention on youth and young adults, since young people tend to be less committed to partisan and ideological views and still open to and interested in alternatives.

-

Finding ways to get people of different ideological persuasions into sustained contact with each other, since simply knowing fellow citizens with different views makes it more difficult to stereotype and demonize them. Actually collaborating with diverse people on some kind of shared goal can be especially helpful.

- Experimenting with new messages and formats that educate polarized adults more effectively.